Books authored

To obtain one or more of the books below please write to ExecSec@CID-world.org

Work in poetry. Poems and songs about work (originals and Greek translation).

Athens, Polytypo, 1984, 110 p.

Editor: Alkis Raftis

Publisher: Polytypo, Athens

Year of publication: 1984

110 pages 24.5 x 17.2 cm

Η εργασία στην ποίηση

Ποιήματα και τραγούδια για τη δουλειά σε ελληνική μετάφραση

Επιμελητής: Αλκης Ράφτης

Εκδότης: Πολύτυπο

Δεινοκράτους 131, Κολωνάκι, 11521 Αθήνα

Τηλ. 210 722 9237

Διάθεση: Θέατρο Ελληνικών Χορών “Δόρα Στράτου”

Σχολείου 8, Πλάκα, 10558 Αθήνα

Τηλ. 210 324 4395, φαξ 210 324 6921

www.grdance.org mail@grdance.org

Ετος έκδοσης: 1984

110 σελ. 24.5 x 17.2 εκ.

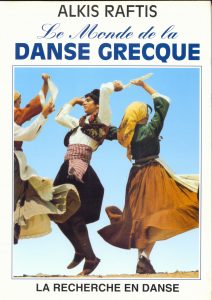

The world of Greek dance. London, Finedawn, 1987, 239 p.

The world of Greek dance. London, Finedawn, 1987, 239 p.

Preface by Prof. Gillian B Ottomley

Original edition by Fin Edawn, London, 1987

Reprinted by the Dora Stratou Dance Theatre

Scholiou 8, Plaka, GR-10558

Athens, Greece

Tel. (30)210 324 4395;

(30)210 324 6188;

fax (30)210 324 6921

www.grdance.org mail@grdance.org

First printing: 1987

239 pages (16 in color) 24 x 16.5 cm

ISBN 960-7589-009

Original hardcover edition reprinted several times as softcover.

The standard introduction to Greek dance, since 1985. The original edition in Greek has been translated to English, French, Italian, Polish. It has been used as required reading at universities, schools, workshops and classes on Greek traditional culture.

With learned introductions to folk music and musical instruments, costumes, customs, history of dance from Ancient Greece till the present, plus guidelines for research.

Includes complete directories of folk dance groups, musicians’ cafés, village festivals, institutions, books, etc.

Dance in poetry. International anthology of poems on dance. Paris, International Dance

Council CID, UNESCO, 1991, 186 p.

Reprinted by the Princeton Book Company, Princeton NJ, USA.

Preface

Dance has meant many things to many poets. Some, like Denise Levertov, see themselves in the role of the dancer:

to leap becomes, while it lasts,

heart pounding, breath hurting,

the deepest, the only joy.

Others, like William Meredith, place themselves in the audience:

/ am but one among your crowd of starers,

One of the blur of shirt-fronts and hands clapping.

There are those who admire the ballerina, as does Norma Farber:

Dancer, how do you rise?

The ground sends me.

Grace suspends me.

While Adrian Mitchell prefers an earthier genre:

….big dancers, they stamp and they stamp fast,

Trying to keep their balance on the globe.

Carl Sandburg wrote some lines for Gene Kelly to tap dance to:

Can you dance a couple of commas?

And bring it to a finish with a period?

Sacheverell Sitwell was enchanted by the Bayaderes:

They sway like young trees with wind upon their leaves

In an airy rapture……..

And Thomas Hardy imagined Grandma Jenny swooping through:

The favourite Quick-step “Speed the Plough” –

(Cross hands, cast off, and wheel)

“The Triumph”, “Sylph”, “The Row-dow-dow”,

Famed “Major Malley’s Reel”…….

The pleasures of dance and of poetry are manifold. Some dancers are happiest with the steps of classical ballet; others prefer jazz or jigs. Some poets choose to describe dancers in sonnets; others in free verse. The choices are numerous. The riches are here for the reader to enjoy.

Selma Jeanne Cohen

INTRODUCTION

This anthology, as is often the case with anthologies, grew out of a personal collection — a few poems on dance encountered by chance and put aside to read again and again. Another collecting passion, postage stamps on dance, will have to wait much longer for publication. These two collections appear to me as complementary. One can find no better way of putting side by side pictures of dance from every country in the world than through postage stamps. And there is no better way of covering the immense spectrum of aspects of dance, than by turning to the poets of the world. Much more than critics, historians or other scholars of dance, poets capture dance as a total phenomenon. No wonder, since dance is at the same time local and universal, ephemeral and eternal.

One of the most intriguing things about dance is that this art form provokes so many different emotions and ideas, and is so rich and powerful to the body as well as to the eyes. Yet, seen in a inter-ethnic and diachronic context, the dominant dance forms of today, the ones usually seen performed in television and theatres, the ones danced in schools and discotheques, seem restricted. The conception of dance within modern Western civilization is, inevitably, very limited since, in other cultures and other time periods, people danced and thought of dance differently. If one’s view of dance is to be enlarged, watching dances from other countries is necessary; furthermore, learning, practising and understanding their meaning.

So much has been written about dance being a universal language, a form of expression that readily crosses frontiers and is easily appreciated by foreign peoples. European Community planners have selected dance for priority support because among the arts dance is a non-verbal, hence convenient language for promoting understanding between nations. Most of the poerns in the following pages suggest that dance is not one language but very many, plus countless local dialects. Each indivual has his own unique dance/speech within his dance/ mother-tongue. Dance Esperantos like ballet or disco may become universal, or disappear like so many verbal and non-verbal languages throughout history.

A central preoccupation of dancers, teachers, choreographers and critics alike concerns quality: how to produce choreography with greater creativity as well as better trained dancers. This book argues, in its own way, for quantity: increased participation in dance. In a world where people gradually accustom themselves to being entertained by others, dance as a popular art faces a long-term threat. Entertainment is becoming synonymous with remaining seated, whether in the theatre, in a restaurant, or in front of the television, passively consuming a programme prepared by others. Sitting is the greatest enemy of dance. The future may bring fewer and fewer people dancing, leaving this experience to highly trained professionals. The ability to use song, music and dance in their simplest forms in order to entertain oneself is being lost.

Looking at the future, the evolution of dance is predictable. One has only to examine music – but also eating and working – to understand that they have undergone the same phases of transformation. Deritualized at first, then repressed as primary needs of the body, their practice is gradually specialized in terms of people, time and space. Next, they are sold as a spectacle and, as such, their consumption must be generalized. The final stage is stockpiling by large corporations through control of reproduction and distribution. In this process, inherent meanings are lost with mere commodities as a result. Dance is obviously becoming fetishized as merchandise, a fact dance ethnographers discover when confronted with cultures where dance remains a ritual. Given a similar perspective, poetry seems to offer a salutary refuge for the future because poetry will certainly be the last art to follow the above course.

Dance poetry is, first of all, poetry of enjoyment. Too much stress is put on creative freedom and technique when referring to theatrical dance, too much importance is given to recreation when speaking of social dance. We tend to forget that dance, as a means of “knowing” one’s partner and one’s self – in the spiritual as well as in the carnal sense – is or should be one of the most enjoyable activities known to humanity. Dance poetry celebrates that fact; and therefore is more often than not likely to arouse or titillate the reader’s appetite for dancing.

Although the specimens presented in this book inevitably reflect the anthologist’s taste, their selection was made with the reader’s pleasure in mind. Poems were not included for their historical, literary or sociological interest. Other criteria used were the broadening of the spectrum as regards dance forms, time periods and approaches to dance. Translations already published were considered, which means that some extraordinary poems in foreign languages will be found in the respective language volume or will await a subsequent volume with new translations in English.

Presenting the poems has been a problem. Aligning chronologically is the most common way used in anthologies, but then relatively few anthologies are international and even fewer are thematic. Chronological order is suitable cnly when recording events within a given frame of reference; in this case a false impression of linear evolution would be created. Arranging geographically, by continent and country of poet, seemed appropriate for local dance forms but did injustice to poets inspired by scenes of imported idioms. Finally, thematic classification (by type of dance or event) proved impossible without imposing arbitrary limits between dance forms. Alphabetical order remained, as both neutral and convenient.

I take this opportunity to express sincere gratitude to so many friends around the world who contributed poems in English or in other languages. I would like to thank Mary Pat Balkus, Professor at Radford University, without whose encouragement and help this work would have remained a few more years in manuscript form.

Alkis Raftis

Dance, culture and society (in Greek). Athens, Dora Stratou Dance Theatre, 1992.

Χορός, πολιτισμός και κοινωνία

του Αλκη Ράφτη

Εκδότης: Αθήνα, Θέατρο “Δόρα Στράτου”, www.grdance.org

Ετος έκδοσης: 1992

167 σελ.

Το βιβλίο αυτό αποτελείται από 17 αυτοτελή κείμενα, τα περισσότερα από τα οποία είχαν δημοσιευτεί προηγουμένως σε περιοδικά ή σε συνέδρια, στην Ελλλάδα ή στο εξωτερικό. Κεντρικός άξονας είναι η θεώρηση του χορού σαν κοινωνικού φαινομένου, με την παράθεση απόψεων πάνω σε ένα ευρύ πεδίο θεμάτων. Τα θέματα αυτά περιλαμβάνουν: την εξέλιξη του φολκλορικού χορού, την εκπαίδευση στον έντεχνο χορό σε ευρωπαϊκή κλίμακα, την εθνογραφική έρευνα στην Ελλλάδα, τον αρχαίο χορό, μέχρι και την ποίηση. Το σημαντικότερο ίσως από τα κείμενα αυτά είναι εκείνο όπου προτείνεται αναλυτικά μια πλήρης παιδαγωγική αντιμετώπιση του προβλήματος της αναβάθμισης του μαθήματος δημοτικού χορού. Με τίτλο “Για μια νέα γενιά δασκάλων…” δίνεται το περιεχόμενο των θεμάτων και των τεχνικών που θα πρέπει να χρησιμοποιήσει ο δάσκαλος για να γίνει το μάθημα δημοτικού χορού πλήρες και να ξεφύγει από την απλή απομίμηση χορευτικών κινήσεων.

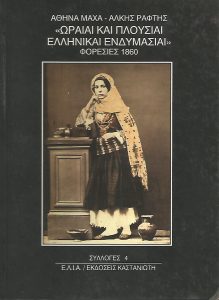

Costumes 1860 (in Greek), with Athena Makha. Athens, Kastaniotis, 1995, 111 p

Costumes 1860 (in Greek), with Athena Makha. Athens, Kastaniotis, 1995, 111 p

“Ωραίαι και πλούσιαι ελληνικαί ενδυμασίαι”

Φορεσιές 1860

Συγγραφείς: Αθηνά Μαχά και Αλκης Ράφτης

ISBN 960-03-1425-X

Εκδότης: Ελληνικό Λογοτεχνικό και Ιστορικό Αρχείο και Καστανιώτης, Σειρά Συλλογές 4

Ετος έκδοσης: 1995

111 σελ. 16.5 x 12

Εισαγωγή

Ελάχιστοι (ή μάλλον ελάχιστες) έχουν ενδιαφερθεί σοβαρά για την ιστορία της παραδοσιακής φορεσιάς στην Ελλάδα. Ενα μέσο τόσο γοητευτικό αλλά και τόσο διεισδυτικό για την κατανόηση της εξέλιξης των τοπικών κοινωνιών έμεινε ανεκμετάλλευτο. Το ιστορικό κατεστημένο πριμοδοτούσε μέχρι πρόσφατα τη μελέτη της “Ιστορίας των πολιτικών γεγονότων”, αποκλείοντας όχι μόνο τους παρακατιανούς κλάδους της “Ιστορίας της καθημερινότητας”, αλλά και πιο καθωσπρέπει προσεγγίσεις, όπως η “Ιστορία των οικονομικών συναλλαγών”.

Η Ιστορία της ελληνικής φορεσιάς – όπως και η Ιστορία της μουσικής, των χορών, των διαλέκτων και τόσων άλλων εκφράσεων του παραδοσιακού πολιτισμού – θα μπορούσε να είναι πολύ πιο πλούσια από τις αντίστοιχες άλλων ευρωπαϊκών χωρών. Αυτό δεν το λέμε από επιπόλαια εθνική αυταρέσκεια, αλλά μετά από σύγκριση με τις άλλες χώρες. Ανάλογο πλούτο είχαν και οι άλλοι λαοί της Ερώπης, απλώς όμως τον έχασαν πριν από την Ελλάδα. Η διακυβέρνηση από ξένους, η απουσία αστικής τάξης, οι μειωμένες επικοινωνίες και η φτώχεια είχαν τουλάχιστον ένα καλό: τα δικά μας χωριά και νησιά κράτησαν την αυτοτέλειά τους μέχρι πρόσφατα.

Μέσα στην περιορισμένη λοιπόν βιβλιογραφία, το έργο και η προσωπικότητα της Αγγελικής Χατζημιχάλη όχι μόνο ανοίγουν το δρόμο, αλλά και δεσπόζουν μέχρι σήμερα. Οι εργασίες των επιγόνων (Τατιάνα Γιανναρά, Κατερίνα Κορρέ, Ιωάννα Παπαντωνίου, για να αναφέρουμε αλφαβητικά τις πιο γνωστές από τις “πανελλήνιες”) εξασφάλισαν τη συνέχεια και εδραίωσαν τη μελέτη, αλλά δεν κατάφεραν να δημιουργήσουν ένα ρεύμα. Λείπει η πολλαπλασιαστική δυναμική, που θα χρειαζόταν για να καλυφθεί το αντικείμενο σε πλάτος και σε βάθος.

Οποιος ενδιαφέρεται να βρει νέα στοιχεία για την ιστορία της παραδοσιακής φορεσιάς στην Ελλάδα έχει μπροστά του την επιλογή ανάμεσα σε διάφορες ερευνητικές προσεγγίσεις. Θα αναφέρουμε τις κυριότερες:

α) Τις φορεσιές που έχουν διασωθεί σε μουσεία, σε συλλογές και στα σεντούκια των σπιτιών. Αυτές καλύπτουν τα τελευταία 100 χρόνια.

β) Τις προφορικές πληροφορίες αυτών που τις φόρεσαν. Κι αυτές αφορούν τα τελευταία 100 χρόνια.

γ) Τις φωτογραφίες – αυτές μάς πηγαίνουν μέχρι 150 χρόνια πίσω.

δ) Αλλες γραπτές πηγές, όπως προικοσύμφωνα, εφημερίδες, λογοτεχνικά και κάθε είδους κείμενα στα ελληνικά – πάλι για τα τελευταία 150 χρόνια.

ε) Τα χαρακτικά, τους ζωγραφικούς πίνακες και τις περιγραφές ξένων περιηγητών του 18ου αλλά κυρίως του 19ου αιώνα. Ας ορίσουμε σχηματικά την περίοδο που καλύπτουν στα τελευταία 200 χρόνια.

Για το διάστημα από τα τέλη του 18ου αιώνα μέχρι την αρχαιότητα υπάρχουν βέβαια άλλες πηγές, αλλά δεν αφορούν πλέον το ίδιο αντικείμενο. Το ίδιο ισχύει και για τη μελέτη της φορεσιάς γειτονικών λαών που επηρρέασαν τους Ελληνες. Πρόκειται για την “προϊστορία” της παραδοσιακής φορεσιάς.

Το βιβλίο αυτό έχει σκοπό να δώσει το έναυσμα για την παρουσίαση των αμέτρητων φορεσιών που είναι αποτυπωμένες στις παλιές φωτογραφίες. Οταν οι πληροφορίες που μπορούν να μας δώσουν διασταυρωθούν με τις άλλες πηγές που αριθμήσαμε παραπάνω, τότε η Ιστορία της ελληνικής φορεσιάς θα έχει ολοκληρωθεί. Οπωσδήποτε, η περισυλλογή των προφορικών πληροφοριών με επιτόπια έρευνα είναι η σπουδαιότερη μέθοδος – και η πιο επείγουσα.

Μιλήσαμε για έναυσμα και για παρουσίαση, γιατί δεν επιχειρούμε μια ενδυματολογική μελέτη δημοσιεύοντας αυτή τη μικρή συλλογή. Θελήσαμε μόνο να ευαισθητοποιήσουμε το ευρύ κοινό και να προσελκύσουμε όσο γίνεται περισσότερους νέους ανθρώπους στον γοητευτικό και απέραντο κόσμο της φορεσιάς.

Οταν ανακαλύψαμε ότι ανάμεσα στους θησαυρούς που έχει συγκεντρώσει στις συλλογές του το Ε.Λ.Ι.Α. υπάρχουν αυτές οι φωτογραφίες, δεν μπορέσαμε να αντισταθούμε στον πειρασμό να τις δημοσιεύσουμε με λίγα σχόλια.

Ολες οι φωτογραφίες της συλλογής έχουν διαστάσεις 9,5 χ 6 εκ. και είναι κολλημένες σε σκληρό χαρτόνι. Εδώ παρουσιάζονται σε μεγέθυνση. Ανήκουν στην κατηγορία των cartedevisite. Αυτό δεν σημαίναι ότι χρησίμευαν για επισκεπτήρια αλλά ότι είχαν μέγεθος επισκεπτηρίου. Ο τύπος αυτός καθιερώθηκε το 1854 στη Γαλλία από τον André Disderi και επέτρεπε για πρώτη φορά την ταυτόχρονη παραγωγή 25 ή περισσοτέρων αντιτύπων με μικρό κόστος.

Από το βιβλίο του Αλκη Ξανθάκη “Ιστορία της ελληνικής φωτογραφίας” μαθαίνουμε ότι στην Αθήνα οι πρώτες φωτογραφίες τύπου cartedevisite τυπώθηκαν το 1860 από τον Αθανάσιο Κάλφα και είχαν αμέσως μεγάλη διάδοση. Ο Κάλφας διατηρούσε φωτογραφείο μαζί με τον ζωγράφο Νίκο Φαρμακίδη μέσα στο ξενοδοχείο “Απόλλων” στην οδο Ερμού. Αλλοι φωτογράφοι της εποχής που αναφέρονται είναι ο Κάρολος Σχήφφερ, ο Πέτρος Μωραϊτης, ο Φίλιππος Μαργαρίτης και ο Ξενοφών Βάθης. Ο κάθε Ελληνας μπορούσε πλέον να κάνει συλλογή από φωτογραφίες διασημοτήτων, με πρώτες των βασιλέων Οθωνα και Αμαλίας.

Αξίζει σ’αυτό το σημείο να υπενθυμίσουμε ότι οι φωτογραφίες της εποχής εκείνης δεν είχαν καθόλου σαν σκοπό τους να αποτυπώσουν μια κάποια “τυπική” μορφή της τότε φορεσιάς. Οι φωτογραφιζόμενοι φορούσαν απλώς τα ρούχα με τα οποία καμάρωναν. Πρόκειται για ιδιαίτερα εύπορα άτομα που, όταν δεν είχαν αποφασίσει να ασπαστούν την ευρωπαϊκή μόδα, διατηρούσαν μεν την φορεσιά του τόπου τους αλλά σε μια εξεζητημένη μορφή της. Οι χειρόγραφες λεζάντες τους είναι κι αυτές αμφισβητίσιμες, γιατί είναι πιθανό να γράφτηκαν από υστερώτερους συλλέκτες.

Αλλη επιφύλαξη αφορά τους χρωματισμούς. Οι φωτογραφίες ήταν βέβαια μονόχρωμες (η έγχρωμη φωτογραφία επεκράτησε περίπου εκατό χρόνια αργότερα), αλλά οι φωτογράφοι συνήθιζαν να τις χρωματίζουν με σινική μελάνη, με κάποια πρόσθετη αμοιβή. Το επάγγελμα του φωτογράφου ήταν τότε συγγενές με του ζωγράφου, πολλοί άλλωστε δήλωναν στις διαφημίσεις τους “φωτογράφος και ζωγράφος”. Δεν είναι λοιπόν καθόλου βέβαιο ότι τις επιχρωμάτιζαν σωστά.

Τελειώνοντας, θα θέλαμε να ευχαριστήσουμε τον Μάνο Χαριτάτο που έθεσε στη διάθεσή μας τις φωτογραφίες και τα αρχεία του Ε.Λ.Ι.Α., τον Γιάννη Μυλωνά για τις πληροφορίες του σχετικά με τις στρατιωτικές στολές και την Αδαμαντία Αγγελή για τη δακτυλογράφηση των κειμένων.

Αθηνά Μαχά & Αλκης Ράφτης

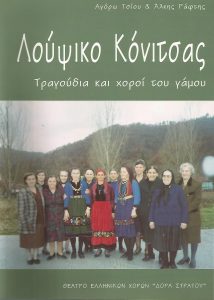

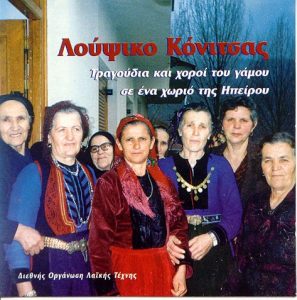

Loupsiko. Wedding dances and songs (in Greek), with Agoro Tsiou.

Athens, Greek Dances Theater, 1997, 143 p. and CD.

Loupsiko, Konitsa

Wedding songs and dances (in Greek)

by Agoro Tsiou and Alkis Raftis

Publisher: Dora Stratou Dance Theatre, Athens, www.grdance.org

143 pages 24 x 17 εκ. + CD

ISBN 960-7204-14-X

Λούψικο Κόνιτσας

Τραγούδια και χοροί του γάμου

Συγγραφείς: Αγόρω Τσίου και Αλκης Ράφτης

Εκδότης: Θέατρο Ελληνικών Χορών “Δόρα Στράτου”

Σχολείου 8, Πλάκα, 10558 Αθήνα

Τηλ. 210 324 4395, φαξ 210 324 6921

143 σελ. 24 x 17 εκ. + CD

ISBN 960-7204-14-X

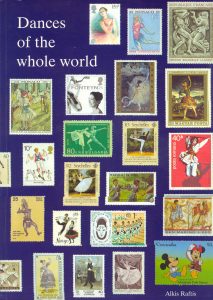

Dances of the whole world. A complete catalogue of stamps.

Athens, Greek Dances Theater, 1998, 77+16 p.

Bronze medal, Kifissia Philatelic Exhibition, Athens, Greece,1999

Bronze medal, World Philatelic Exhibition, Nürnberg, Germany, 1999

Bronze medal, Brno 2000 National Stamp Exhibition, CzechRepublic, 2000

Silver bronze medal, 5th National Philatelic Literature Exhibition, Ottawa, 2000

Silver bronze medal, Chicagopex 2000 Exhibition, Rosemont, Illinois, 2000

Silver bronze medal, Cyprus-Europhilex 2002, Cyprus, 2002

Dances of the whole world

on postage stamps. A complete catalogue

Author: Prof. Dr. Alkis Raftis

Preface: Prof. Dr. Roderyk Lange

Publisher: Dora Stratou Dance Theater

Scholiou 8, Plaka, GR-10558 Athens, Greece

tel. (30)210 324 4395;

fax 210 324 6921

Under the auspices of the International Dance Council CID, UNESCO

Publication date: 1998

Pages 77+16 colour

ISBN 960-7204-15-8

Price: 14 euros

– A complete catalogue of the 3,000 postage stamps on dance

– 93 pages, format A4 (30.5 x 22.5 cm), 16 pages illustrated in color

– Catalogue numbers: Scott, Stanley Gibbons, Michel, Yvert et Tellier

– Stamps arranged by country, year of issue, denomination

– Short description of the dance scene, plus philatelic information

– All the 267 countries, past and present, on the globe

– All genders of dance, from prehistoric to ancient to ballet, to traditional to modern to disco

– Indispensable for collectors and dance historians

– Authored and prefaced by two of the world’s most respected dance scholars.

Cover T000140

Bronze medal, Kifissia Philatelic Exhibition, Athens, Greece,1999

Bronze medal, World Philatelic Exhibition, Nürnberg, Germany, 1999

Bronze medal, Brno 2000 National Stamp Exhibition, CzechRepublic, 2000

Silver bronze medal, 5th National Philatelic Literature Exhibition, Ottawa, 2000

Silver bronze medal, Chicagopex 2000 Exhibition, Rosemont, Illinois, 2000

Silver bronze medal, Cyprus-Europhilex 2002, Cyprus, 2002

Preface

It is well known that iconography plays a vital role in tracing dance activities in the past. When there are no descriptions of the dance progression available, when no music survives the pictorial representations of dance scenes supply us at least with a visual record, proving, that certain dance activities existed. Even if a picture on its own does not convey the movement, one may deduce from it some information on the type and style of dancing during a certain period. For this reason iconography is a much respected source material in dance research.

Alkis Raftis has collected postal stamps with dance representations for a long time. This domain was until now quite neglected. It represents, though, an important document of the appreciation of dance in our time, and is an indication of the recognition of its growing status.

The author has drawn together extensive material in this publication, and catalogued it. For this labor of love future generations of dance researchers will certainly be grateful. Roderyk Lange

Introduction

The present catalogue represents the first attempt to approach dance in a truly global perspective. In issuing postage stamps, every country strives to project its image inland and abroad. Accordingly, for every single country one can see now the vision it has of its own dance.

No book exists dealing with dance in all the countries of the world. “History of dance” books number by the thousands, but they mostly deal with ballet and modern dance. Their focus is always on theatrical dance of the European tradition, with a couple of odd chapters on other dance forms. When treating non-theatrical or non-European dances, they cannot help to see them in a superficial or ethnocentric perspective. On the other hand, there are many books dealing with dance in one country or one small region, and so many more could be written before local dance idioms disappear under the pressure of television-diffused culture.

Dance teachers and dance group leaders know very well that, among the persons who take up dance in their teens, in infinite fraction remains when in their twenties. From then on, they very rarely practice dance, if at all. Some become occasional spectators of dance performances, even less keep in touch by reading dance magazines or books.

Collecting dance stamps can keep a great number of young – and less young – people abreast with the art, bring them in contact with other enthusiasts around the world, while offering an encyclopedic knowledge of the subject. This catalogue is addressed primarily to dance teachers who, if not ready to adopt the hobby themselves, should drop the idea to their students.

Thematic stamp collecting is a hobby for dozens of millions of persons around the globe but, among the hundreds of themes selected, dance is a rarity. One wonders why, especially since so many young persons attend dance schools or take part in folk dance groups, not to mention those frequenting dance halls or discothèques. Collecting dance stamps, besides the general benefits of stamp collecting, broadens one’s understanding of dance and enhances the pleasure of practicing or watching dance.

In compiling this catalogue, several questions have arisen, involving a number of choices as to which stamps should be included.

– Is it dance? In a great number of scenes it is not clear whether the persons depicted are dancing or simply adopting a dance-like posture. We have included these stamps, guided by the context of the scene, and noted our doubt by a question mark.

– What is dance? Scholars have struggled for ages with definitions of dance. It is still not clear how to classify borderline cases, like ice-dancing (more correctly called figure-skating), rhythmic gymnastics or water-dancing. Some people even claim animals dance. Definitely, not every rhythmical movement is dance, even when it is accompanied by music. Otherwise, a military parade would be dance. The definition we propose is Dance is organized expressive movement. When the esthetic expression through body movement as such is dominant, then it is not dance. We believe that when the primary object is physical exercise, it should be classified under “sports”, even when it involves graceful movement with music. Not to disappoint some collectors, we have included a number of such stamps.

– What about dance-related objects? The most common case is dance masks, but also ballet shoes, tambourines, castanets and other objets used by dancers and clearly implying dance. When they are depicted outside a dance scene, we have included them only when the context makes it clear that they are used to point specifically to dance (for example as symbols of a dance festival).

– Should dance-music be included? The answer was easily negative – dance music is not dance. Stamps with composers, musical instruments, opera houses, scores etc. belong to the sphere of music stamp collecting, enjoying a great number of collectors and abundant literature.

Fortunately, most of the stamps compiled here denote dance clearly. To make things even simpler for dance stamp collectors, we have used this rule of thumb: When in doubt, we include a stamp if at least one of the four catalogues consulted mentions dance in its description.

This catalogue is updated constantly to include new issues of stamps and revise or add catalogue numbers. An edition in CD-ROM form is under preparation. It will include the contents of this catalogue, plus color illustrations of more than 1,000 stamps, plus extensive notes of the dances and dancers mentioned.

The data has been arranged in fields:

COUNTRY – The country issuing the stamp

YEAR – Year of issue

DENOMINATION – Face value of the stamp

DESCRIPTION – Short description of the dance scene

SCOTT – Scott catalogue number

GIBBONS – Stanley Gibbons catalogue number

MICHEL – Michel catalogue number

YVERT – Yvert et Tellier catalogue number

NOTES – Additional information, mainly philatelic. This field is used to give distinctive signs of the stamp, such as color, air mail, overprinting, souvenir sheets etc., to facilitate recognition, especially in case of similar issues.

Dance 1900

Greek turn of the century postcards portraying dance

(in Greek)

Author: Alkis Raftis

Publisher: Dora Stratou Dance Theater

Scholiou 8, Plaka, GR-10558 Athens, Greece

tel. (30)210 324 4395;

(30) 210 324 6188;

fax 210 324 6921

Publication date: 1999

237 pages in color 19.5 x 28.5 cm.

ISBN 960-7118-13-8 (9607118138)

157 postcards dating around 1900, depicted at enlarged size, with detailed historical comments in Greek.

The scholarly work (in Greek). Athens, Way of Life Publications, 2000, 104 p.

The scholarly work (in Greek). Athens, Way of Life Publications, 2000, 104 p.

Author: Alkis Raftis

Publisher: Way of Life Publications, Athens

Distributor: Dora Stratou Dance Theater

Scholiou 8, Plaka, GR-10558

Athens, Greece

tel. +30 210 324 4395;

+30 210 324 6188;

fax +30 210 324 6921

Year of publication: 2000

104 pages 24 x 17 cm

ISBN 960-7118-19-7 ( 9607118197 )

Η μελετητική εργασία

Βοήθημα για την εκπόνηση

και την παρουσίαση

Συγγραφέας: Αλκης Ράφτης

Εκδότης: Εκδόσεις “Τρόπος Ζωής”

Διάθεση: Θέατρο Ελληνικών Χορών “Δόρα Στράτου”

Σχολείου 8, Πλάκα, 10558 Αθήνα

Τηλ. 210 324 4395, φαξ 210 324 6921

www.grdance.org mail@grdance.org

Ετος έκδοσης: 2000

104 σελ. 24 x17 εκ.

ISBN 960-7118-19-7 ( 9607118197 )

Isadora Duncan and the artists (in Greek with English supplement). Athens, Way of Life Publications & Dora Stratou Dance Theatre, 2003, 222+79 p.

Publisher: Dora Stratou Dance Theatre

Scholiou 8, Plaka, GR-10558 Athens, Greece

Tel. +30 210 324 4395, fax +30 210 324 6921

www.grdance.org mail@grdance.org

Publication date: 2004

222+79 pages 29.5 x 22.5 cm

ISBN 960-7118-90-1 (Main volume in Greek)

ISBN 960-7118-90-1 (companion volume in English)

Price: 35 euros (the two volumes)

10 euros (as eBook)

Works or texts by 106 artists of her time. Original research in archives during 10 years brought to light many works of art as well as passages from rare books describing Isadora Duncan’s unique dance. In the complete absence of films, this album is the best possible view of her dancing. Full colour, large format reproductions of paintings, sculptures, sketches (no photographs) by world-acclaimed artists. Passages from famous writers translated to English and Greek from several languages, by the one of the world’s most prolific writers on dance.

INTRODUCTION

In 1903 Isadora Duncan came with her brother Raymond to Athens, where she had dreamed of settling and founding her school, the school from which would spring the first dancers of Modern Dance, inspired by the dance of Ancient Greece. They started to build a house, which never became the school that Isadora had dreamt of.

Today, however, a hundred years later, this memory-laden house, a monument in the worldwide history of dance, has been completed by the Municipality of Vyronas and is already operating as the “Centre of the Study of Dance”, open to all the current developments in dance, and we all hope that it will be dedicated to the cultivation of a modern dance that will be as close as it can be to Ancient Hellenism.

This provides the opportunity to present today something that has been missing from international bibliography: an anthology of the works of the important artists who knew Isadora Duncan and immortalised her.

Alkis Raftis

The Duncan phenomenon

The bibliography on Isadora Duncan is enormous, but the writing is almost entirely descriptive. It consists either of biographies recounting the events of her life, or of reviews and impressions of her performances, which inevitably have a large dose of subjectivity. My own position is that of sociologist and historian.

I see Isadora Duncan more as a social phenomenon. I am interested in finding out:

– What reasons led to her emergence and the emergence of other similar dancers at that time, even though these may not have made history?

– What factors shaped her thinking and generally her personality?

– How can society’s reception of her be explained? In particular: who formed her public, or rather, who formed her publics, since they consisted of specific and disparate groups? What did each of these groups find in Duncan?

– What was Duncan’s “message”? What was the space she came to fill in the society of that time? How did she pass her message on to her public, and how did her public’s messages reach her?

Origin and development

– Middle-class family, artistically educated parents.

– She grew up in deprived circumstances, without a father.

– She left school before she had completed her elementary education.

– She taught herself French and German.

– She taught herself dance and music.

– She studied philosophy, theatre.

– She wore Greek chitons at a time when women usually wore corsets and several petticoats.

Dance

– She danced barefoot and half-naked, when serious stage dancing was synonymous with “tutu” and “pointes”.

– She was the first to use the musical works of great composers that had not been written for dancing.

– She appeared on stage alone; it was only later that her young pupils sometimes accompanied her.

– She used the simplest of costumes, with no scenery.

– She did not perform choreographies; she improvised, or rather gave a spontaneous interpretation of the music.

– She attempted to dance to Byzantine music, a practice so far ahead of her time that no one dared to follow it for a whole century afterwards.

– In spite of the sensual dimension of her dance, the most serious critics insisted that it was not provocative.

– Today’s choreographers have begun to take movements and gestures from everyday life. Duncan was ahead of them in this by about 80 years.

Her impact on society

What were the social groups that constituted her public?

– Royalty and heads of state

– Artists

– Intellectuals and students

– The upper middle class (in Europe and America)

– Workers and farmers (in the Soviet Union)

A list of leaders of state who attended her performances:

– President Roosevelt of the USA,

– The King of Bulgaria, with whom she was said to have had an affair,

– King George I of Greece, who, when he heard of her triumphant performance at the Municipal Theatre in 1903, asked her to perform in the Royal Theatre, where he went with his entire family,

– Prime Minister Eleftherios Venizelos, who invited her to settle in Greece for the second time in 1920.

– The Empress of Germany Augusta Victoria, who saw one of her performances in Berlin and criticized her barefoot pupils,

– Vladimir Ilyich Lenin, leader of the Soviet Union, who showed more enthusiasm than all the others.

Morality

Sceptics will say that such enormous success could be due to the fact that Duncan offered a very daring spectacle, at the same time covering it with the alibi of avant-garde art. Men in the audience could, without pangs of conscience, feast their eyes on a statuesque body, whose nakedness was only minimally hidden by her classic chitons and expressive movements.

They should recognise however that Isadora Duncan’s success led to the appearance of many other dancers with equivalent physical advantages, more sensuous dancing and often more undisguised nudity. Ruth Saint Denis in America, Maud Allan in England, Adorée Vilani in France were among the best known. For many others, dance was nothing more than an excuse for moving their bodies provocatively, though few of them had more to show than their curves.

There was no lack of competition in this field, and Duncan would not have stood out if her body were the main attraction for audiences. Besides, she herself often refused to collaborate with impresarios who offered her tempting fees, if she suspected that they meant to present her as the “half-naked dancer”.

The reader might think that I sympathise with the established view that regards sensual dance as inferior. For instance, dancers of all other kinds (theatrical, folk, ballroom) unanimously look down at dancers of “Anatolian dance” (oriental, belly dance, dance of the seven veils, cabaret etc.). This is an unfair and superficial view that should somewhere else be objectively refuted. Sensual dance, in all its nuances, is equally serious, just as artistic and undoubtedly beautiful; it is socially useful, and historically older than other kinds of dance.

Women’s rights

Revolutions – like all social phenomena – are a combination of two factors. On one hand the ripeness of circumstances, development to the point where radical change is necessary and feasible. On the other hand, the emergence of one or more people who sense the need for change, personify it and fight for it until they bring it about. We should see Duncan’s revolution in this way.

Isadora declared unequivocally that she supported the rights that should belong to every woman:

– To be married or not.

– To make love to whatever man she wished.

– To have children or not.

– To look after her children herself or not.

– To travel on her own.

– To express her political opinions.

Anyone with a knowledge of the conditions prevailing the start of the twentieth century will realise how explosive such opinions were then.

Politics

In spite of the fact that she was not interested in politics, Isadora had the instinct and the daring to follow whatever was most progressive in the ideas of her time. We should not be prejudiced by the picture we have today of the those political currents; the important thing is that she espoused the most avant-garde ideas at that time. It took a sharp instinct to choose them and particular courage to follow them.

In Greece, for example, she sided with Eleftherios Venezelos, who was then in conflict with the King. In Russia, at a time when almost all the Russian dancers and choreographers were leaving for Europe and America, she alone moved against the current: she sided with the Bolsheviks from the beginning and worked hard to help the Revolution with her dance. She supported her views not only with words, as usually happens in politics, but with harsh personal sacrifices: when Anna Pavlova and Vaslav Nijinsky were living in the most luxurious hotels in Nice and Paris, she was touring the remotest areas of Soviet Russia in conditions of indescribable poverty.

Greek spirit

Isadora and her brother Raymond were not the first people to worship Greece. A hundred years before them, many eminent foreigners had fallen under the spell of the classical beauty of ancient Greece, and had remained faithful to it in spite of the bitterness the actual Greece soaked them with. Once again the Duncans went further than the others: they translated the Ancient World into everyday action, they tried it out on their bodies. They wore chitons and sandals that Raymond had made, they danced trying to bring to life the scenes on the ancient vases.

Most important of all, they actually came to live in Greece. We should not forget that many of the Greek-worshippers before them, starting with Winkelman, had never visited Greece even as sightseers. The Duncans came for the first time in 1903. It was Raymond who played the main part in this, returning at every opportunity for sixty years.

On two other occasions Isadora attempted to settle in the country, even though this would have amounted to sure professional suicide. What could an international personality expect from the Greece of 1903? A faraway country, small, poor, destroyed by wars and strife, where there were neither dance schools, nor professional dancers, nor even the conditions for the development of theatrical dance. Sikelianos’ efforts themselves twenty years later failed because Greece was too backward to accept them.

Ecology

Nowadays, eating natural foods and generally living in harmony and contact with nature is something that is supported by ecologists, and it seems reasonable enough. One hundred whole years have passed however, since the days when Raymond Duncan recommended it. Only ten years ago, such ideas were still daring and generally unknown to many people. Imagine how avant-garde such ideas were then. The ecological movement was ninety years behind Raymond Duncan, and still has not caught up with him. For Duncan turned ecology into everyday action: he wove his own clothes on the loom, and he himself made the sandals that he wore, his furniture and his implements. Today’s “green” organisations would not dare to advise the public to follow him.

And as if this was not enough, the Duncans went even further. They discovered that there was an ecological kind of music, the “natural scales”, which had passed from ancient music into Byzantine hymns. Today’s ecologists have not yet suspected this, that there exists a kind of “ecology of music”. Isadora dared to dance to this music, and Raymond taught it for decades, but their efforts came to nothing because they were so far ahead of their time.

I mention Isadora more than Raymond because she is the one who became famous. Brother and sister were always close and one influenced the other, which is why we can talk of the “Duncan phenomenon” from a historical point of view. Raymond won no acclaim because he moved in duller spheres and was more down-to-earth. He too, however, was just as pioneering in his own way.

Suffice it to say that he engaged successfully in dramatic art, poetry, painting, weaving, sculpture, singing, sandal-making, building, wood-carving, as well as European and Byzantine music. He taught all these things – and perhaps others that I have missed – first in Athens and later, until his death in 1967, at the “Academy” he founded in Paris, occasionally giving shows in New York. It would be an omission not to mention (as a hint to the present situation in Kossovo) the fact that after the Greek army entered Albania in 1914, he went to Saranda and helped the locals cope with the misery left by the war. Conditions were so bad there that his wife Penelope, sister of Angelos Sikelianos, became ill and eventually died. It is a great injustice that this great philhellene has not been honoured for his wide-ranging service to Greece.

Dance

There is little need to speak of the crucial importance that the emergence of Duncan had on the development of dance. It is a platitude to say that she is one of the greatest dancers, if only because there is no book on dance history that does not devote several pages to her. Quite a few people would dispute, however, that she was the greatest figure of all. It is worth noting, though, who such people might be.

They are those who stick with whatever technique they were taught and feel the need to defend it. Those who do not have the wide culture or the discriminating sensitivity to see beyond the narrow frontiers of their kind of dance (academic, modern, jazz, character etc.) and to appreciate dance as an art that encompasses all the planet and all ages. In this huge polymorphism, every individual’s technique appears insignificant, while Duncan’s “non-technique” seems great.

I believe that if dance à la Duncan did not spread as much as other schools or fashions it is due to the fact that it was vehicle for an anti-commercial outlook. It was not a “product” suitably “packaged” so that it would “sell”. It did not have “secrets”; it did not have preordained exercises, nor a framework that a dance teacher could declare to possess in order to attract pupils. Duncan’s dancing was based mainly on a deep understanding of dance, of the human body and its expressiveness, of a sense of theatre. Still more, Duncan’s dancing was the outcome of a worldview, which is a feature no one could claim for some of the more usual techniques.

Some dance historians throw the blame on Duncan’s pupils, asserting that they were not equal to continuing her work. Others use the fact that the “Duncan school” has comparatively few representatives today as a criterion to show that her worth was limited.

I will be in the minority in asserting that Duncan’s contribution was not only enormous but also unique in the world history of dance. We should not confuse her with the other dancers, Nijinsky, Pavlova or Saint-Denis: Duncan was something more than a great dancer. We should distinguish her from the great choreographers, Fokine, Balanchine and Graham: Duncan created something more than choreographies.

Isadora Duncan was the greatest because she opened the way for the others we mentioned and for all the other dancers and choreographers. They all came after her, they were influenced by her, and they recognised it more or less. Before her there was only a sterile academic dance, which needed her contribution in order to become fertile again.

She was a complete dancer. The others dedicated their life to dance: she dedicated her dance to life. The others said many things with their dance, but outside their dance they had nothing to say. She, however, brought the revolution to dance and to every other aspect of her life. She set dance on its feet and brought it face to face with the other arts. She stood as an equal with artists and politicians, with philosophers and scholars, having her own point of view, the point of view of a dancer about life and art.

In the pages that follow we try to give a picture of the feeling that Isadora’s dance left on the artists of her times.

Alkis Raftis

ISADORA DUNCAN – HER LIFE

1877

Angela Isadora Duncan was born in San Francisco on 26th May 1877. Her mother was Mary Isadora (Dora) Grey, the daughter of Thomas Grey, who had fought in the Civil War, and had risen to the rank of Colonel. After the War he was appointed a harbour official in San Francisco and finally became a member of the California House of Representatives. Isadora’s father was Joseph Charles Duncan, a businessman who was thirty years older than her mother. They had four children: Mary Elizabeth, Augustin, Raymond and Isadora. Isadora was just five months old when her father’s bank went bankrupt and he himself disappeared to avoid the consequences. From then on, Mary Duncan started to work in order to support her children, while they grew up in deprived circumstances, unsupervised, in a spirit of independence and with a sense of responsibility. In their family environment they learnt to love the arts, playing drama and music in their home.

1887

Isadora left school when she was about ten years old and started to give ballroom dancing lessons to the children of the neighbourhood, helped by her brothers and sister and with her mother at the piano. From then on, she used to read a great deal, a habit she kept up for the rest of her life. In her dancing she must have been much influenced by the ideas of François Delsarte, which were then finding fertile soil in America. Delsarte was the first who studied gestures and put forward a system based on natural, expressive movements.

1895

She went with her mother to Chicago, where she danced for the first time in public, performing Mendelssohn’s “Spring Song”. The theatrical entrepreneur Augustin Daly engaged her in his company in New York, where she took several dance lessons with the well-known ballerina Maria Bonfanti.

1896

She started giving individual performances in theatres and at gatherings in private homes, with the music of Ethelbert Nevin, who himself played the piano. The public were amazed that she dared to dance with bare hands and feet, as well as by her unprecedented free and expressive dance.

1897

She took part in performances of Daly’s company in London, where she had dancing lessons with Katti Lanner. She continued to give dancing lessons to children.

1899

The hotel where the Duncan family were staying caught fire while Isadora and her sister Elizabeth were giving a lesson. By keeping calm they managed to get all their young pupils out, but all their possessions were burnt. She left with her brothers and sisters for London, where she danced at gatherings of art lovers, coming to know various scholars and artists. She went to theatre performances, and studied the Greek sculptures in the British Museum.

1900

She went with her mother to Paris, where her brother Raymond was already staying. With him she studied the representations of ancient dance on Greek vases and in sculptures of the Louvre. She was impressed by the Universal Exposition, especially by the works of Rodin and the performances of Japanese dance. She danced in salons and gave lessons.

1901

She gave recitals in Monte Carlo and in London, with dances inspired by Ancient Greece, Renaissance Italy and contemporary music. The critics gave her a favourable reception. The dancer Loïe Fuller included her in her troupe travelling to Berlin, Leipzig, Munich and Vienna.

1902

In Budapest Isadora gave solo performances in the theatre Urania, dancing to music by Strauss and Liszt, with great success. It was at this time that she first made love, with the young actor Oscar Beregi. Afterwards she parted from Beregi and went to Vienna, where she recovered from a short illness. She danced very successfully in Munich. Her public, mainly young people and students, adored her. After every performance they dragged her carriage to her hotel, where they sang under her windows.

1903

She danced in Berlin and gave her famous lecture on the subject “The dance of the future”, in which she presented her ideas. The text circulated widely in various languages, and is still considered the manifesto of modern dance as well as of the women’s liberation. She returned to Paris, where she gave several less successful performances at the Sarah Bernhardt Theatre. The critics found the dancing charming and interesting, but not serious enough. She was offered a new tour of Germany, but refused.

1903

Her brother Raymond organised a family trip to Greece. From Brindisi they arrived in the island of Lefkada, and from there they went on by caique to Kravasara (today called Amphilochia) where they disembarked and knelt and kissed Greek soil. They called at Agrinio, Missolonghi and Patras, and arrived in Athens. There they bought a stretch of land on the hill of Kopanas (today in the Municipality of Vyronas), which was then open grazing land, and started to build a house, using plans inspired by the Palace of Agamemnon. They wore chitons and sandals and studied ancient Greek art intensively, under the guidance of the archaeologist and scholar Alexander Philadelpheus. They discovered that the ancient Greek music had survived in Byzantine chants, and formed a choir under the direction of Constantine Psachos. Isadora danced in the Municipal Theatre on the 28th of November, where the public, mainly students, gave her a standing ovation. By royal invitation, she gave a second performance on the 11th of December, this time in the Royal Theatre before King George I and all his family, the French writer Pierre Loti and the cream of Athens society. She left for a period in Europe with her choir under the direction of Panaghiotis Tzaaneas.

1904

Her performances were intended to lead to the revival of ancient tragedy, but the public wanted something lighter than Aeschylus’s “The Suppliants”. In vain Isadora gave long talks before each performance, introducing the subject. After performances in Vienna, Munich and Berlin, she disbanded the Greek choir. Her impresario urged her to do a tour of Germany where success was assured, but she preferred to settle down in Berlin, where she was learning German and studying philosophy, especially Nietzsche. Cosima Wagner suggested that she should dance at the Wagner Festival in Bayreuth. She danced the lead in “Tannhäuser”, accompanied by ballet dancers. Public response was disappointing, but the critics found it an interesting experience. She did a tour in Germany. In Berlin she fell in love with the stage designer and theatre innovator Edward Gordon Craig, son of the great English actress Ellen Terry. It was this year that she went to Russia for the first time and gave a performance in Saint Petersburg with music entirely by Chopin. The public and the critics gave her an enthusiastic reception.

1905

She returned to Russia and danced in Moscow. She watched ballet performances and met the great dancers Anna Pavlova and Mathilda Kschessinska, the stage and costume designer Bakst, the producer Diaghilev and the choreographers Marius Petipa and Michail Fokine. Fokine admired her and found her an inspiration for his future choreographies. She danced in Kiev and Moscow, where the public, mostly students, artists and intellectuals, received her with enthusiasm. She returned to Berlin and founded a school with her sister Elizabeth. Twenty young girls were selected from many candidates to be boarders, and, in addition to the usual programme of school subjects, attended lessons in free dance, music, singing, elocution, painting and pottery. The Empress Augusta Victoria attended one performance by Isadora and her pupils, but found the sight of their bare feet unacceptable, out of keeping with the strict morals of the age.

1906

A period with Craig in Germany, Belgium and Holland. She visited the Scandinavian countries. She danced with success in Warsaw and in other Polish cities. It was in Holland in September that she gave birth to her first child, Deirdre. She continued in Holland, until she finally collapsed with exhaustion. She went to Florence, where Craig was doing the sets for “Rosmersholm” with the famous Italian actress Eleonora Duse in the lead.

1907

Craig had tired of his stormy life with her and left her so that he could work in the theatre without distraction. After a period of recuperation in Nice, Isadora danced in Holland, Sweden, Germany and Switzerland. The continued successes brought her plenty of money, but her expenses were always huge: she stayed in the most expensive hotels and was supporting Craig, the baby and its governess, her mother, her sister and the school and its pupils. At the same time, she always received less than was due to her, because of her inability to handle financial matters. She continued her tour: Holland, Warsaw, Munich, Russia. In Moscow she became close friends with Constantin Stanislavsky.

1908

She gave several performances at the Gaieté-Lyrique theatre in Paris, but without success, since public attention was focussed on the concerts of Russian music that Sergei Diaghilev was organising then. She started a tour in the United States, but seeing the indifference of the public, she cut it short and returned to New York. There she met Walter Damrosch, the conductor of the New York Symphony Orchestra, and gave a recital with the 80-member orchestra at the Metropolitan Opera House. The programme included excerpts from Gluck’s “Iphighenia in Aulis”, Beethoven’s Seventh Symphony, and Wagner’s “Tannhäuser”. It was a great success, which was continued at performances in other cities.

1909

Instead of exploiting her triumph in America, she returned to Paris, where her pupils now were. She again gave performances at the Gaité-Lyrique theatre, despite the fact that Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes were appearing triumphantly in the same season and were monopolising the attention of dance lovers. Famous artists such as Jean-Paul Lafitte, André Dunoyer de Segonzac, Jules Grandjouan and Antoine Bourdelle were inspired by her performances. She began a relationship with Paris Singer, a 42-year-old American millionaire with five children, son of the founder of the sewing-machine manufacturer. She gave performances in Russia and in America.

1910

Although she was pregnant, she left again, this time together with Singer, for a series of performances in America with Walter Damrosch and the New York Symphony Orchestra. Her advancing pregnancy worried the public, and made it necessary for her to cut her tour short. After a cruise on the Nile on Singer’s yacht, she returned to the French Riviera, where she gave birth to a little boy they named Patrick. Singer insisted that they should get married, but she refused to betray her convictions about the freedom of women. She tried to make a quiet life in Singer’s property in England, but the tedium drove her into the arms of her pianist André Caplet, although in fact she considered him particularly ugly.

1911

She went to live with her children in Paris, and gave two recitals at the Châtelet Theatre. She gave a tour in the United States.

1912

She was reconciled with Singer, but their relationship remained stormy, with frequent quarrels. Together they planned the building of a theatre where Isadora and her brothers could present ancient drama with Craig, Duse and other great artists they had come to know. But disagreements between the architect and Craig did not allow the plan to proceed.

1913

She gave a series of performances in Russia with the pianist Hener Skene. It was in this year that her two children were drowned in the Seine. After a happy family meal, they had sent the children home in the car. On the way the engine stalled and the chauffeur got out to start it with the starting-handle. But the handbrake gave way, and the car rolled and plunged into the river.

1913

For a change of environment, she went to Corfu, from where her brother Raymond and his wife Penelope, sister of poet Angelos Sikelianos, were helping the Greeks in North Epirus to re-establish themselves after the catastrophes of the Balkan War. She made a short journey with Penelope to Constantinople, and then returned to Paris. She stayed in the house of Eleonora Duse in Viareggio in Italy. Duse persuaded her to return to dancing in order to forget the death of her children. She met a young Italian sculptor and had a short erotic adventure that helped her to recover her spirits.

1914

Singer bought her a hotel building in Paris, with 200 rooms and 80 bathrooms, so that she could fulfil her old dream – a dancing school. They called it Bellevue, because of its view of the Bois de Boulogne. She selected fifty children of eight or nine and entrusted their education to six of her old students who had come from the school her sister Elizabeth was running in Germany. With Stanislavsky’s help she also brought ten children from her school in Moscow. She did little teaching herself because she was pregnant after her affair in Italy. Her child died immediately after it was born. In August the First World War broke out. Isadora handed over the school building to be an army hospital and left for Normandy to convalesce. She attempted to commit suicide by walking into the sea but was saved by her doctor, with whom she cohabited. She left for America. In New York, her six oldest students gave a performance in the Metropolitan Opera House, with Schubert’s “Ave Maria”.

1915

At her next performances she danced the “Marseillaise” and made fiery speeches urging the Americans to come into the War on the side of the French. She tried to raise money to support her school, but her performances were very expensive. In “Oedipus Rex”, in which her brother Augustin played the main role, she used 80 musicians and a choir of 100. Her financial difficulties forced her to leave.

1915

She arrived with her students in Naples, and from there she went on to Switzerland, and finally to Athens, where Raymond was. The house in Kopanas was still half-finished, so they stayed in the Hotel d’Angleterre. Greece was undecided about entry into the War. Prime Minister Venizelos was on the side of the Allies, while King Constantine sympathised with Germany. Isadora moved the crowd to enthusiasm by singing the “Marseillaise” in Constitution Square, and with a dance led a march to Venizelos’ house. She returned to Switzerland, where she left her students, and went on to Paris.

1916

In vain she tried to support her students by giving performances in Paris and Switzerland. She set out with her brother Augustin for a period in Argentina, Uruguay and Brazil. The pianist Maurice Dumesnil accompanied her. She returned alone and deeply in debt to New York. Singer, in spite of the fact that they had separated, helped her financially. She gave a triumphant performance at the Metropolitan Opera House.

1917

She returned to her homeland California after 22 years’ absence and gave performances with the pianist Harold Bower, with whom she had a love affair. She left for London. Her six students now gave performances in New York without her, something which particularly worried her.

1918

She returned to Paris. She fell in love with the English pianist Walter Rummel, who was ten years younger than she was. They lived happily together and gave performances. When the war ended, she wrote to her students asking them to come to France to dance with her. She tried to find money to restart her school. She could not manage it, and had to sell the Bellevue building to the French government. Incapable of negotiation, she accepted a comparatively insignificant sum, with which she bought a house in Paris.

1920

Full of happiness and optimism as a result of her affair with Rummel, she decided to realise her old dream of settling in Athens. She hurriedly repaired the house in Kopanas, and went to live there with Rummel. He however fell in love with her student Anna. Isadora had promised the Greek government that she would prepare a thousand dancers for a “Festival of Dionysos”, and held rehearsals every day in the Zappeion – which prime minister Eleftherios Venizelos allotted her – with music from Beethoven’s Seventh Symphony and the Scherzo from Tchaikovky’s Sixth Symphony. But there was a change of government and Duncan found herself without support. She had to leave for Paris and from there went on to London. Three of her students decided to go to America. In London she met the great writer Bernard Shaw. It was said that she suggested that he should have a child by her, a child who would be exceptional since it would inherit his mind and her body. Shaw is then supposed to have replied, “What if it should inherit my body and your mind?” But Shaw later denied this celebrated anecdote, saying that he could not have said any such thing, since he particularly respected her for her brain.

1921

She gave successful performances in London and Brussels with Rummel at the piano, but finally he went out of her life together with Anna. Isadora accepted the invitation of the Soviet government to found a dance school in Moscow. Her friends did what they could to dissuade her, having heard the most frightful things about the Bolsheviks and the situation in Russia, but she was full of enthusiasm for a new start. She arrived in Moscow accompanied by her student Irma and discovered that the situation was indeed dramatic. The Minister of Education Anatoly Lunacharsky promised her every help. Her first appearance was at the Bolshoi theatre, with 3,000 seats, and in the presence of Lenin. She danced Tchaikovsky’s “Pathetic” Symphony and the Slavonic March, finishing with the “International”, which brought the audience to their feet, singing enthusiastically. Lenin himself stood up and applauded, singing and shouting “Bravo”.

1922

She fell passionately in love with the already famous 26-year-old Russian poet Sergei Essenin, with whom she always communicated by means of an interpreter, since he spoke nothing but Russian. They married and left for Berlin and then for Paris. Isadora asked that 25 students should come from her school to perform with her, but the Soviet government would not give them permission to travel. They left for the USA, where the reception was negative from the start, on account of the anti-communist hysteria of the time. She began a series of performances in the bigger cities. The artists worshipped her but the public were discouraged by the long speeches in favour of Russia that Duncan insisted on giving after every performance. Essenin was often drunk and created serious scenes. They returned to Europe.

1923

After an absence of fifteen months they returned to Moscow. Isadora started tours in the Soviet Union, while Essenin disappeared with another woman.

1924

Isadora continued her tours, under great difficulties on account of the poverty and disorganisation of the country, but with enthusiastic reception by the public. In Moscow, she taught in her school and gave magnificent performances in stadiums with the participation of hundreds of dancers whom she had trained in expressive dance. She left for performances in Berlin, leaving the management of her school in Moscow to her pupil Irma. She settled in Nice, making frequent visits to Paris, where Raymond had created a school and handicraft workshops on the ancient Greek model. His pupils regularly wore chitons and sandals, ate natural foods, wove on the loom, and performed ancient drama.

1925

She heard news of Essenin’s suicide. She continued her efforts to bring dancers from her school in Moscow to Nice, and hired a hall in Nice where she gave a few performances. She continued to face financial difficulties, and lived on contributions from her friends and admirers. She turned down Cecil de Mille’s proposal to make a cinema film of her life, and so today there is no live documentary of her dance. But she needed to find money to live on, and she agreed to write her memoirs. These were published in many languages after her death, with the title “My Life”, but with serious distortions by the publisher.

1926

The nervous strain from the continuous effort of facing her difficulties made her ill with internal haemorrhages. She had to sell her house in Paris, but in the end never received the money.

1927

She gave a triumphant recital at the Mogador theatre in Paris, with the Pasdeloup orchestra under the direction of Albert Wolff. She danced to music by Franck, Schubert and Wagner.

On 14th September, she was killed in an accident in Nice. The long scarf she was wearing tangled in the wheels of the car and wrapped itself round her neck. Her funeral in Paris was attended by a crowd. Her body was cremated, and her ashes placed next to those of her children in the cemetery of Père Lachaise.

Translated from the Greek by Christopher Copeman

and published in the English supplement of the album “Isadora Dyncan and the artists”

Η βιβλιογραφία για την Ντάνκαν είναι μεν τεράστια, σχεδόν όμως στο σύνολό της είναι περιγραφική. Πρόκειται είτε για βιογραφίες που απαριθμούν τα γεγονότα της ζωής της, είτε για κριτικές και εντυπώσεις από τις παραστάσεις της, που αναπόφευκτα έχουν μεγάλη δόση υποκειμενικότητας. Η δική μου θεώρηση είναι εκείνη του κοινωνιολόγου-ιστορικού.

Βλέπω την Ιζαντόρα Ντάνκαν περισσότερο σαν ένα κοινωνικό φαινόμενο. Με ενδιαφέρει να βρω:

– Ποιοι είναι οι λόγοι που οδήγησαν στην εμφάνισή της και στην εμφάνιση άλλων ανάλογων χορευτριών εκείνη την εποχή, έστω κι αν εκείνες δεν έγραψαν ιστορία.

– Ποιοι παράγοντες διαμόρφωσαν την σκέψη και γενικά την προσωπικότητά της.

– Πώς εξηγείται η υποδοχή της από το κοινό. Αναλυτικά: ποιο ήταν το κοινό της, ή μάλλον ποια στον πληθυντικό, μια και πρόκειται για συγκεκριμένες και ετερόκλητες κοινωνικές ομάδες. Τι ήταν εκείνο που βρήκε στη Ντάνκαν η κάθε μία από αυτές τις ομάδες.

– Ποιο ήταν το “μήνυμα” της Ντάνκαν, ποιο ήταν το κενό που ήρθε να καλύψει στην κοινωνία της εποχής της. Με ποιους τρόπους το μήνυμα αυτό περνούσε στο κοινό και με ποιους άλλους τρόπους τα μηνύματα του κοινού έφταναν στην Ντάνκαν.

Προέλευση και εξέλιξη

– Αστική οικογένεια, καλλιτεχνικά μορφωμένοι γονείς.

– Μεγάλωσε με στερήσεις, χωρίς πατέρα.

– Εγκατέλειψε το σχολείο πριν τελειώσει το Δημοτικό.

– Εμαθε μόνη της γαλλικά και γερμανικά.

– Εμαθε μόνη της χορό και μουσική.

– Μελέτησε φιλοσοφία, θέατρο.

– Φόρεσε ελληνικούς χιτώνες όταν οι γυναίκες φορούσαν κορσέδες και πολλά μεσοφόρια.

Χορός

– Χόρεψε ξυπόλυτη και μισόγυμνη, όταν ο σοβαρός σκηνικός χορός ήταν ταυτόσημος με tutu και pointes.

– Χρησιμοποίησε πρώτη μουσικά έργα των μεγαλύτερων συνθετών, που όμως δεν ήταν γραμμένα για χορό.

– Ηταν ολομόναχη στη σκηνή, μόνο αργότερα συνοδευόταν καμιά φορά από μικρές μαθήτριές της.

– Είχε απλούστατα κοστούμια, και κανένα σκηνικό.

– Δεν εκτελούσε κάποια χορογραφία, αυτοσχεδίαζε, ή μάλλον απέδιδε αυθόρμητα τη μουσική.

– Δοκίμασε να χορέψει με βυζαντινή μουσική, κάτι τόσο πρωτοπορειακό που δεν τόλμησε να το ακολουθήσει καμία επί έναν ολόκληρο αιώνα.

– Παρά τη σαρκική διάσταση του χορού της, οι πιο σοβαροί κριτικοί επέμεναν ότι δεν είναι προκλητικός.

– Οι σημερινοί χορογράφοι άρχισαν να παίρνουν κινήσεις και χειρονομίες από την καθημερινή ζωή. Η Ντάνκαν είχε προηγηθεί σ’ αυτό κατά 80 χρόνια.

Κοινωνικός αντίκτυπος

Ποιες ήταν οι κοινωνικές ομάδες που αποτελούσαν το κοινό της:

– Βασιλείς και αρχηγοί κρατών

– Καλλιτέχνες

– Διανοούμενοι και φοιτητές

– Μεγαλοαστοί (στην Ευρώπη και Αμερική)

– Εργάτες και αγρότες (στη Σοβιετική Ενωση).

Ας απαριθμήσουμε τους αρχηγούς κρατών που πήγαν στις παραστάσεις της:

– Ο Πρόεδρος των ΗΠΑ Ρούσβελτ,

– Ο βασιλιάς της Βουλγαρίας, με τον οποίο λέγεται ότι είχε σχέσεις.

– Ο βασιλιάς της Ελλάδας Γεώργιος ο 1ος, που όταν έμαθε για τη θριαμβευτική της παράσταση στο Δημοτικό Θέατρο το 1903 της ζήτησε να δώσει παράσταση στο Βασιλικό Θέατρο όπου πήγε με όλη την οικογένειά του.

– Ο πρωθυπουργός Ελευθέριος Βενιζέλος, ο οποίος την κάλεσε να εγκατασταθεί στην Ελλάδα για δεύτερη φορά το 1920.

– Η αυτοκράτειρα της Γερμανίας Αυγούστα Βικτωρία, η οποία είδε μια παράστασή της στο Βερολίνο και επέκρινε τις ξυπόλυτες μαθήτριές της.

– Ο Βλαντιμίρ Ιλιτς Λένιν, ηγέτης της Σοβιετικής Ενωσης, που έδειξε το μεγαλύτερο ενθουσιασμό από όλους τους προηγούμενους.

Ηθική

Μερικοί καχύποπτοι θα πουν πως τέτοια τεράστια επιτυχία μπορεί να οφειλόταν στο ότι η Ντάνκαν προσέφερε ένα θέαμα πολύ τολμηρό, καλύπτοντάς το συγχρόνως με το άλλοθι της πρωτοποριακής τέχνης. Οι άντρες θεατές μπορούσαν να χορταίνουν χωρίς τύψεις το θέαμα ενός αγαλματένιου κορμιού, που η γύμνια του ελάχιστα κρυβόταν από τους αρχαιοπρεπείς χιτώνες και τις εκφραστικές κινήσεις της.

Θα πρέπει να γνωρίζουν όμως ότι η εμφάνιση της Ντάνκαν έδωσε το σύνθημα για μια πληθώρα χορευτριών με ανάλογα σωματικά προσόντα, με πιο αισθησιακό χορό και συχνά με πιο απροκάλυπτη γύμνια. Η Ρούθ Σαιντ Ντένις στην Αμερική, η Μωντ Αλλαν στην Αγγλία, η Αντορέ Βιλανί στη Γαλλία ήταν από τις πιο γνωστές. Για πολλές άλλες, ο χορός δεν ήταν παρά μια πρόφαση ή ένα μέσον για να κουνήσουν ερεθιστικά το κορμί τους, ενώ λίγες ήταν εκείνες που είχαν κάτι να δείξουν πέρα από τις καμπύλες τους.

Δεν έλειπε λοιπόν ο ανταγωνισμός στο θέμα αυτό, πράγμα που αποδεικνύει ότι δεν θα ξεχώριζε η Ντάνκαν αν το σώμα της ήταν κυρίως αυτό που τραβούσε το κοινό. Αλλωστε, η ίδια πολλές φορές αρνήθηκε να ακολουθήσει τους ιμπρεσάριους που την προσέφεραν δελεαστικές αμοιβές, όταν διαισθανόταν ότι σκόπευαν να την παρουσιάσουν σαν την “μισόγυμνη χορεύτρια”.

Ας μην νομιστεί ότι συμμερίζομαι την καθιερωμένη αντίληψη που θεωρεί τον αισθησιακό χορό σαν κατώτερο χορευτικό είδος από τα άλλα. Για παράδειγμα, οι χορεύτριες όλων των ειδών χορού (θεατρικού, δημοτικού, σαλονιού κ.ά.) περιφρονούν ομόφωνα τις χορεύτριες του “ανατολίτικου χορού” (οριαντάλ, χορός της κοιλιάς, χορός των 7 πέπλων, καμπαρέ κλπ.). Είναι μια άποψη άδικη και επιπόλαια που θα πρέπει κάπου αλλού να ανατραπεί επιστημονικά. Ο αισθησιακός χορός, σε όλες τις αποχρώσεις του, είναι εξ ίσου σοβαρός, ανάλογα τεχνικός, αναμφισβήτητα ωραίος, κοινωνικά χρήσιμος και ιστορικά παλαιότατος σε σύγκριση με τα άλλα είδη χορού.

Δικαιώματα της γυναίκας

Οι επαναστάσεις – όπως όλα τα κοινωνικά φαινόμενα – είναι συνδυασμός δύο παραγόντων. Αφ’ ενός της ωρίμανσης των συνθηκών, της εξέλιξης μέχρι του σημείου όπου η αλλαγή είναι αναγκαία και εφικτή. Αφ’ ετέρου, της εμφάνισης ενός ή περισσοτέρων ανθρώπων που διαισθάνονται την ανάγκη για αλλαγή, την ενσαρκώνουν και αγωνίζονται μέχρι να την υλοποιήσουν. Ετσι λοιπόν, θα πρέπει να δούμε την επανάσταση Ντάνκαν.

Η Ιζαντόρα δήλωσε απερίφραστα ότι διατηρεί τα δικαιώματα που πρέπει να αποκτήσει κάθε γυναίκα:

– Να παντρεύεται ή όχι

– Να κάνει έρωτα με όποιον άντρα θέλει

– Να κάνει παιδιά ή όχι

– Να φροντίζει τα παιδιά της ή όχι

– Να ταξιδεύει μόνη της

– Να εκφράζει τις πολιτικές της αντιλήψεις.

Μόνο κάποιος που έχει γνώση των συνθηκών στις αρχές του αιώνα μπορεί να συνειδητοποιήσει πόσο εκρηκτικές ήταν τέτοιες αντιλήψεις τότε.

Πολιτική

Παρ’ όλο που δεν ενδιαφερόταν για την πολιτική, η Ιζαντόρα είχε την διαίσθηση και την τόλμη να ακολουθήσει ό,τι πιο προοδευτικό παρουσιάστηκε στην εποχή της. Ας μην επηρεαζόμαστε από την εικόνα που έχουμε σήμερα για τις τότε πολιτικές δυνάμεις, το σημαντικό είναι ότι εκείνη την εποχή ήταν ό,τι πιο πρωτοποριακό υπήρχε. Χρειαζόταν οξεία διαίσθηση για να τις επιλέξει κανείς και ιδιαίτερη τόλμη για να τις ακολουθήσει.

Στην Ελλάδα για παράδειγμα, ήταν με το μέρος του Ελευθέριου Βενιζέλου, που τότε βρισκόταν αντιμέτωπος με τον βασιλιά. Στη Ρωσία, την ώρα που όλοι σχεδόν οι ρώσοι χορευτές και χορογράφοι έφευγαν προς την Ευρώπη και την Αμερική, μόνη εκείνη κινήθηκε αντίθετα στο ρεύμα: πήγε με τους μπολσεβίκους από την πρώτη στιγμή και δούλεψε σκληρά για να βοηθήσει την επανάσταση με το χορό της. Δεν ήταν μόνο με λόγια που υποστήριζε τις απόψεις της, όπως συνήθως γίνεται στην πολιτική, αλλά με σκληρές προσωπικές θυσίες: Οταν η Αννα Παύλοβα και ο Βασλαβ Νιζίνσκυ ζούσαν στα πολυτελέστερα ξενοδοχεία της Νίκαιας και του Παρισιού, εκείνη περιόδευε στις πιο απομακρυσμένες περιοχές της Σοβιετικής Ενωσης μέσα σε συνθήκες απερίγραπτης ανέχειας.

Ελληνικό πνεύμα

Δεν ήταν οι μόνοι που λάτρεψαν την Ελλάδα. Εκατό χρόνια πριν από την Ιζαντόρα και τον Ραίημοντ, αμέτρητοι επιφανείς ξένοι γοητεύτηκαν από το αρχαίο κάλλος και του έμειναν πιστοί παρ’ όλα τα φαρμάκια που τους πότισε η νεότερη Ελλάδα. Οι Ντάνκαν όμως, ακόμα μια φορά ξεπέρασαν τους άλλους: αυτοί μετέτρεψαν σε καθημερινή πράξη την Αρχαιότητα, την δοκίμασαν πάνω στο σώμα τους. Φορούσαν χιτώνες και σανδάλια που έφτιαχνε ο Ραίημοντ, χόρευαν προσπαθώντας να ζωντανέψουν τις παραστάσεις των αρχαίων αγγείων.

Το σημαντικότερο: ήρθαν να εγκατασταθούν στην Ελλάδα. Ας μην ξεχνάμε ότι πολλοί από τους μέχρι τότε ελληνολάτρες, με πρώτο τον Βίνκελμαν, δεν είχαν έρθει στην Ελλάδα ούτε καν σαν περιηγητές. Οι Ντάνκαν ήρθαν για πρώτη φορά το 1903. Στο θέμα αυτό πρωτοστατούσε ο Ραίημοντ, ο οποίος ξαναγύριζε με κάθε ευκαιρία επί 60 χρόνια.

Αλλες δύο φορές δοκίμασε να εγκατασταθεί εδώ η Ιζαντόρα, αν και αυτό ισοδυναμούσε με βέβαιη επαγγελματική αυτοκτονία. Τι θα μπορούσε να περιμένει μια διεθνής προσωπικότητα από την Ελλάδα του 1903; Μια χώρα μακρυνή, μικρή, φτωχή, κατεστραμένη από τους πολέμους και τις πολιτικές διχόνοιες, όπου δεν υπήρχαν ούτε σχολές χορού, ούτε χορευτές, ούτε καν οι συνθήκες για την ανάπτυξη της τέχνης του θεατρικού χορού. Οι προσπάθειες του Σικελιανού 20 χρόνια αργότερα απέτυχαν κι αυτές γιατί η Ελλάδα βρισκόταν πολύ πίσω για να τις δεχθεί.

Οικολογία

Το να τρως φυσικές τροφές και γενικά να ζεις σε αρμονία και επαφή με την φύση είναι κάτι που το προτείνουν σήμερα οι οικολόγοι και φαίνεται αρκετά λογικό. Πάνε όμως 100 ολόληρα χρόνια από τότε που το πρότεινε ο Ραίημοντ Ντάνκαν. Πριν από 10 μόνο χρόνια αυτές οι ιδέες ήταν πολύ τολμηρές και γενικά άγνωστες στον πολύ κόσμο. Φανταστείτε πόσο πρωτοποριακές ήταν τότε. Το οικολογικό κίνημα ακολουθεί με διαφορά φάσης 90 ετών τον Ραίημοντ Ντάνκαν, και πάλι δεν μπορεί να τον φτάσει. Γιατί ο Ντάνκαν έκανε την οικολογία καθημερινή πράξη: ύφαινε τα ρούχα του στον αργαλειό, έφτιαχνε ο ίδιος τα σανδάλια που φορούσε, τα έπιπλά του και τα σκεύη του. Οι σημερινές οργανώσεις των οικολόγων δεν θα τολμούσαν να προτείνουν στο κοινό να τον ακολουθήσει.

Και σαν να μην ήταν αρκετά αυτά, οι Ντάνκαν έφτασαν ακόμα μακρύτερα. Ανακάλυψαν ότι υπάρχει μια κάποια οικολογική μουσική, οι λεγόμενες “φυσικές κλίμακες” που πέρασαν από την αρχαία στη βυζαντινή μουσική. Αυτό οι σημερινοί οικολόγοι δεν το έχουν ακόμα υποψιαστεί, ότι υπάρχει δηλαδή μια κάποια “οικολογία της μουσικής”. Η Ιζαντόρα τόλμησε να χορέψει μ’ αυτή τη μουσική, ο Ραίημοντ την δίδασκε επί δεκαετίες, αλλά και αυτές οι προσπάθειες χάθηκαν γιατί ήταν εξαιρετικά πρωτοπόρες.

Αναφέρομαι περισσότερο στην Ιζαντόρα γιατί εκείνη έγινε διάσημη. Τα δυο αδέλφια ήταν πάντα κοντά και το ένα επηρέαζε το άλλο, γι αυτό μπορούμε να μιλάμε για το “φαινόμενο Ντάνκαν” από ιστορική άποψη. Ο Ραίημοντ δεν κέρδισε τη δόξα γιατί κινήθηκε σε χώρους πεζούς και ήταν πιο προσγειωμένος. Ηταν όμως κι εκείνος ανάλογα πρωτοπόρος με τον τρόπο του.

Θα αναφέρω μόνο ότι ασχολήθηκε με επιτυχία με τη δραματική τέχνη, την ποίηση, τη ζωγραφική, την υφαντική, τη γλυπτική, την ταπητουργική, την τυπογραφία, τη φιλοσοφία, τις επιχειρήσεις, το τραγούδι, τη σανδαλοποιία, την οικοδομική, την ξυλογλυπτική, καθώς και την ευρωπαϊκή και τη βυζαντινή μουσική.

Ολα αυτά – ίσως μου διαφεύγουν άλλα – τα δίδασκε αρχικά στην Αθήνα και κατόπιν μέχρι τον θάνατό του το 1967 στη “Ακαδημία” που είχε ιδρύσει στο Παρίσι, δίνοντας κατά καιρούς παραστάσεις στη Νέα Υόρκη. Θα ήταν παράλειψη να μην αναφέρω, γιατί έχει κάποια επικαιρότητα, το ότι ο Ραίημοντ Ντάνκαν ήταν αυτός που το 1914 μετά την απελευθέρωση της Ηπείρου από τον ελληνικό στρατό πήγε στους Αγίους Σαράντα και βοηθούσε τους Βορειοηπειρώτες να αντιμετωπίσουν τη δυστυχία που τους άφησε ο ελληνοτουρκικός πόλεμος. Ηταν τόσο άσχημες οι συνθήκες που η γυναίκα του Πηνελόπη, αδελφή του Αγγελου Σικελιανού εκεί αρρώστησε και τελικά πέθανε. Είναι μεγάλη αδικία να μην έχει τιμηθεί αυτός ο μεγάλος φιλέλληνας για το έργο του και την παντοειδή προσφορά του στην Ελλάδα.

Η συμβολή της στο χορό

Είναι περιττό να μιλήσουμε για την κεφαλαιώδη σημασία που είχε για την εξέλιξη του χορού η εμφάνιση της Ντάνκαν. Το ότι ανήκει στους μεγάλους του χορού είναι κοινοτοπία, και μόνο από το γεγονός ότι δεν υπάρχει βιβλίο ιστορίας του χορού που να μην της αφιερώνει μερικές σελίδες. Το ότι όμως ήταν η πιο μεγάλη μορφή θα βρεθούν αρκετοί να το αμφισβητήσουν. Ας προσέξουμε όμως ποιοι είναι αυτοί.

Είναι όσοι μένουν προσκολλημένοι στην όποια τεχνική διδάκτηκαν και αισθάνονται την ανάγκη να υπερασπιστούν. Αυτοί που δεν έχουν την πλατιά καλλιέργεια ή την λεπτή ευαισθησία για να δουν πέρα από τα στενά όρια του δικού τους είδους χορού (ακαδημαϊκός, μοντέρνος, τζαζ, καρακτέρ κλπ.) και να αντιληφθούν τον χορό σαν τέχνη που αγκαλιάζει όλη την υφήλιο και όλες τις εποχές. Μέσα σ’ αυτήν την τεράστια πολυμορφία τεχνικών, η τεχνική του καθενός φαίνεται μηδαμινή, ενώ η μη-τεχνική της Ντάνκαν φαίνεται μεγάλη.

Το ότι ο χορός α-λα Ντάνκαν δεν εξαπλώθηκε όπως άλλες σχολές ή μόδες, πιστεύω ότι οφείλεται στο ότι ήταν φορέας μιας αντι-εμπορικής νοοτροπίας. Δεν ήταν ένα “προϊόν” κατάλληλα “συσκευασμένο” ώστε να “πουλάει”. Δεν είχε “μυστικά”, δεν είχε προκαθορισμένες ασκήσεις, κάποιο πλαίσιο που μια δασκάλα χορού να μπορεί να ισχυρισθεί ότι εκείνη μόνο κατέχει και να τραβήξει μαθήτριες. Ο χορός της Ντάνκαν βασίζεται κυρίως σε μια αντίληψη για τον χορό, για το ανθρώπινο σώμα και τις εκφράσεις του, για τη θεατρικότητα. Ακόμα περισσότερο, ο χορός της Ντάνκαν είναι φορέας μιας κοσμοθεωρίας, κάτι που δεν μπορεί να πει κανείς για ορισμένες από τις διαδεδομένες τεχνικές.

Ορισμένοι ιστορικοί του χορού ρίχνουν την ευθύνη στις μαθήτριες της Ντάνκαν, υποστηρίζοντας ότι έφταιξαν αυτές που δεν ήταν αντάξιες να συνεχίσουν το έργο της. Αλλοι χρησιμοποιούν σαν κριτήριο το ότι η “σχολή Ντάνκαν” έχει σήμερα ελάχιστους εκπροσώπους, για να εμφανίσουν ότι η αξία της ήταν περιορισμένη.

Εγώ θα μειοψηφίσω υποστηρίζοντας ότι η συνεισφορά της Ντάνκαν όχι μόνο τεράστια ήταν αλλά και μοναδική στην παγκόσμια ιστορία του χορού. Ας μην την συγχέουμε με τους άλλους χορευτές, τον Νιζίνσκυ, την Παύλοβα, την Σαιντ-Ντένις – η Ντάνκαν ήταν κάτι παραπάνω από μεγάλη χορεύτρια. Ας την ξεχωρίσουμε από τις μεγάλες χορογράφους, τον Φοκίν, τον Μπαλανσίν, την Γκράχαμ – η Ντάνκαν έκανε κάτι παραπάνω από χορογραφίες.