Articles on dance and culture

Dance in Greece

Raftis, Alkis: “Dance in Greece“, Λαογραφία newsletter of the international greek folklore society, Vol. 2, No. 8, 2-7, California, U.S.A., 1985.

1. Roman And Byzantine Period

Greek classical antiquity came to an end with the Roman conquest in the 2nd century B.C. The Romans adopted many of the achievements of Greek civilization and made great use of its artists and scholars throughout the Roman Empire. Greek dancers found themselves addressing a wider audience, spread over a large area, constituting various peoples, in most part not understanding their language. Not bound anymore to the moral and aesthetic precepts of the small Greek city, they turned to easy tricks to please their patrons: dances became burlesque, lascivious, comic or frightening. The unity that characterized the Greek notion of musike, comprising song, dance and instrumental music in one whole, was fragmented into separate parts of the performance. Song remained in Greek language for some time, sung by a passive chorus as an interlude. Music became independent by the addition of several instruments to the lyre and flute, so as to form a little orchestra.

Dance, loose from word and melody, became pantomime. Although mimic dances abounded in the Greek antiquity, pantomime is the hallmark of the Greco-Roman period. Performers became famous for thier ability to relate entire stories with their gestures and postures. They wore masks, lavish clothes and jewelry, they were frequently effeminate and they resorted to vulgar jokes and obscenities. Thus dancers became professionals of low status rather than public servants and dance lost its religious and educational character to become a spectacle of mere entertainment.

It was inevitable that the Christian church would attack this form of dancing, especially in the Byzantine Empire, virtually a theocratic state. Most of what is known about dance during the Byzantine era (5th to 15 centuries) comes from the prohibitions and exhortations of the orthodox church. Texts by the church fathers and the synods refer to dancing as demonic, blasphemous and abominable. The very fact that this polemic persisted proves that dance remained popular.

It is important to note, though, that the Eastern Christian church made no distinction between dancing by professional dancers (jugglers, circus and theater actors, prostitutes, slaves) and rural dancing by villagers. Stage dancing must have been somehow obscene in Constantinopleand the other urban centers, though our sources are exclusively ecclesiastical. Mimes and daners lived a disordserly life and made it a point to ridicule Christian rites. On the other hand dancing in villages conserved its nature as a public ritual, albeit with pagan and naturalistic elements.

In spite of the constant pressure by the church, emperors hesitated to prohibit dancing for fear of arousing the public sentiment. Popular dancing continued in village celebrations on saints’ days and there were instances where dancing is reported inside the churches on Christmas. Dances were very common after Easter, during marriage feasts, on birthdays. Soldiersdanced during pauses of their training, chariotteers danced their victories, the court danced on the emperor’s birthday, large public dances erupted as a relief after the passing of difficult moments.

Written sources do not supply any actual description of dancing. From a multitude of dispersed phrases and some paintings in churches it can be deduced that as a rule the pattern was the round, chain dance. Men and women danced separately, but there is mention of mixed dances. Sometimes the leading dancer would take the line into a sinuous form. It was frequent for the dancers to hold kerchiefs or veils and wave them, to stamp their feet on the ground and clap their hands. Women dancers, especially professionals, held wooden or metal cymbals. The dancers or the musicians sang known songs or improvised. A distinguishing feature of stage dancers was their shirt-sleeves, very tight up to the elbow and then very large and long so that they could be waved and enhance the movements of the hands. The most common instruments used for dancing was the flute, also the guitar, little drums and tambourines.

There is no evidence of dances of the court or of the upper classes of this period. Unlike Western Europe of the Middle Ages where a variety of local rulers looked to Rome for their religious authority, the Eastern Empire was a centralized state where

political and religious authority ran in parallel, confirms its continuity and establishes the conclusion that time has worked on it entirely in a reductive way. That is, the variety and richness of dance situation contracted gradually and slowly, with very little adoption of additional elements. This is explained by the following traits of the evolution of Greek culture since the antiquity:

The Greek countryside has villages that have always lived in economic and cultural autonomy. The frequent passage of conquering armies on the mainland and pirates along the coasts, the difficulty of communications even between neighboring areas or islands, the poor yield of the soil that caused a chronic expiration of the most dynamic element of the population, the absence of a local ruling class that would enhance integration, these were the main reasons for the extent of self-sufficiency of Greek villages as compared with villages in other countries, who could have a constant contact with a neighboring urban center.

Thus, customs evolved in a slow rate in every village and small region, and with them dancing as well. Local festivities on religious occasions conserved their ritual character as an affirmation of in-group identity. Social control through the observance of customs remained strict as a defense against the rulers and a way to preserve ties with emigrating relatives. A common dance in the village square or churchyard was the only occasion for a general meeting and review of the condition of families, for the open encounter between boys and girls and for celebration after a harsh daily life. Marriages were such occasionson a smaller scale. Preparations and celebrations lasted several days or several weeks, following an elaborate pattern of prescribed customs including dancing at various moments.

2. Rural Popular Dance

Traditional dance is defined here as dance transmitted from one generation to the next by the continuous immersion in one cultural group, that is not through formal teaching. Folk dance, on the other hand, consists of traditional dance forms practiced within a non-traditional society for educational, performing or other purposes. In this sense, traditional dancing is still widely practiced in the Greek countryside, although a steady decline is evident since the Second World War, as a result of modernization. Young people have left the villages to find jobs in the towns or abroad, roads have been opened to previously inaccessible areas, television sets have proliferated, tourists flood the coasts every summer and discotheques sprout in the smallest towns. Customary ways of entertainment have changed, while government policy towards dance has been one of marked neglect.

The Civil War in the Forties forced a large part of the rural population to find refuge in towns and to look back to life in the village as one associated with backwardness. The after-war generation does not consider popular dance as its own. Traditional dances tend to become gradually a matter for folk dance groups, with the subsequent loss of feeling and emphasis on the spectacular.

There are 500 folk dance groups around the country, and as many in the Greek communities abroad. The State gives them a token financial support and they raise the necessary funds to have costumes made by donations from wealthier citizens. These groups have a repertoire of dances from their own region, as they cannot afford more sets of costumes. There are two State-supported permanent theaters giving daily performances of dances from various regions. One is kept by the Dora Stratou group in Athens and the other by the Nelly Dimoglou group in Rhodes. The Lyceum of Greek Women, the first organization to start giving performances of folk dances back in the Thirties, has branches in all towns, each one having its own dance group.

Costumes, music and dance styles differ greatly among regions and among Greek sub-cultures, sometimes even among nearby villages. Generally speaking, one could distinguish at least twenty regions and sub-cultures, each one of them having at least ten dances of its own, and this division could go even further. This stems from the fact that, apart from geographical entities, there are ethnic groups of Greeks that have resettled in other areas. Pontic Greeks, for example, have lived for centuries along the North coast of Asia Minor until they established themselves in entire villages dispersed in Macedonia, the most notable regions when it comes to dance are: Thrace, Macedonia, Epirus, the Southern Mainland, the Ionian Islands, the Aegean SeaIslands, the DodecaneseIslands, Crete, Cyprus. Other ethnic groups, irrespective of. the region of settlement are the Arvanites, the Vlachs, the Pomacs, the Sarakatsani and resettled Greeks from the Asia Minor coast, the Black Sea coast and Northern Thrace. Some dances are common between neighboring regions, although the style of dancing is unmistakably different. Songs and music are quite distinct, too. Thus, a performing group will not present dances from another region unless it has the costumes of this region. There is no one truly all Greek dance, although some dances have come to be widely practiced.

By far the most common dance form is the Syrtos dance. The name indicates a “drawing” action and this explains the basic notion of a dance being “drawn” by the first dancer, as if the leader pulls a line of dancers behind him. The term Syrtos was found on an ancient inscription but there is no indication of how it was danced. In modern Greece it became a generic name for a dance in open circle with a walk-like step. The basic Syrtos is in 2/4 measure, with one long and two short steps to the right. Theleader has freedom to improvise and to coil and uncoil the line of dancers into various patterns. One particular Syrtos, called Kalamatianos, is in 7/8 measure and originates from the Southern mainland. It was gradually adopted by the other regions and came to be considered as a national dance as it evoked the part of Greecethat was first liberated from Turkish rule. Several other dancers are called Pidiktos (i.e. hopping) to distinguish from Syrtos that has necessarily a shuffling step.

In the most common handhold each dancer simply holds the hands of the two dancers next to him, arms down or bent at the elbows. Another way is to hold hands cross-wise, that is between alternative dancers in the line (as in the Trata of Megara or the Sousta of Rhodes), mostly used in women’s dances. Men’s dances sometimes involve holding each other’s shoulder (like in the Pentozali of Crete and the Gaida of Macedonia) and a tendency to stay in a straight line rather than a circle. Other holds are by the elbow (as in Tsakonikos of Peloponese and Pogonissios of Epirus) or by the belts (as in Zonaradikos of Thrace).

Dancing face-to-face (Karsilamas or Antikrystos) or solo (Beratis dance) is rare and seems an influence from the Greeks of Asia Minor. Couple dances (like Ballos) are an exception, presumably of Western origin. The rule for public dancing was the solemn circular dance, while improvising figures and dancing of small groups was decent only in family celebrations at home. In general, dancers move the upper parts of their bodies very slightly, by contrast with Middle Eastern dancers. Similarly, Greek women do not dance alone in front of men.

The first dancer in the line holds a position of honor, the dance is considered his. In some areas, after the Easter Sunday mass the priest leads the first dance in the churchyard or around the church as a token of benediction of the celebration. In a marriage feast the bride leads the first dance, the bridegroom and the inlaws. Usually all the participants take turns at leading the dance, each one also asking the musicians to play the tune of his preference and paying them for it. A woman will not lead a dance unless her father, brother, or husband asks and gives an order to the musicians. As a rule, the head of the family passes an order to the musicians when he wants to dance with his family or friends. It was considered a deliberate offense to enter into someone else’s dance, many fights and stabbings started this way. It was also improper to ask a girl to the dance unless engaged to marry.

The order in which dancers align themselves in the circular dance was of great importance, especially in the opening dance of a celebration. The most common pattern is for men first, according to age, followed by the women also according to age, then the children. Thus, the only way to advance up the line was when an older person could not dance any more. In some villages a girl may advance in the line if she marries before an older girl. Since holding the hand of a woman in public was considered improper, a problem arose as to who would be the connecting link between the men and the women. This was solved by placing there a child or an aged couple. When the entire family dances as a group, the internal hierarchy is followed in the order of succession, this causing sometimes disputes between cousins.

In earlier times, when village people were too poor to pay a musician, it was common for the Sunday afternoon dances to be held with the girls singing. But big public dances on prescribed dates and marriage celebrations were always held with instrumental music. The most widespread instruments are the bagpipe, called gaida on the mainland (or tsambouna on the islands, where it has no drone), the three-stringed lyra (gradually replaced by the violin), the shawn (zourna, usually played by gypsies) and the clarinette (klarino), that replaced the flute. Percussion is provided by a big drum (up to 1 meter in diameter, called daouli), a small pottery drum (toumbeleki), or tambourine which was mainly a woman’s instrument. Most of the instrumentplayers on the mainland are still gypsies, but their own musical idiom did not influence local music, as in other countries. Instruments were made by the musicians themselves, types and methods of construction varying widely among regions.

Of special interest are the fire-dancing rites in three Macedonian villages on St. Constantine’s Day, where participants dance on glowing coals until they reduce them to ashes. Also, the carnival celebrations in Naoussa, Skyros, Zakynthos and other areas, where villagers wearing masks, bells, sheepskins and various disguises perform ritualised mimic and comic dances.

3. Urban Popular Dance

By the middle of the 19th century, an idiomatic form of music and dancing appeared among the lower social strata in ports of the Aegean Sea. In the poorer neighborhoods of cities like Istanboul, Smyrna, Salonica and Syra had gathered thousands of outcasts leading a life of misery and lawlessness. They developed their own means of expression breaking away -though taking elements from – the rural tradition, the Turkish culture and the European culture of the upper classes. This genre – eventually called rebetika – gained increasing momentum and social acceptance to become one century later the hallmark of Greek music internationally.

Originating in the tavernas and coffee-houses frequented by sailors, peddlers, jobless and petty criminals, lyrics lament frustrated loves, reject bourgeois lifestyle, idealised bravado actions and project the counter-values of a marginal social group. Music is played by string instruments: mainly the mandolin-like bouzouki and the smaller baglama, also violin, santouri (dulcimer) and guitar. The musicians who played on a stage along one wall of the neighborhood cafe, with a small space in front of it where patrons could dance. The orchestra appeared there every evening, unlike folk musicians who played only on festive days in the open air, and it included women singers who occasionally danced too.

The most common dance is the Zeibekiko, in 9/4 meter, a solo impovisation dance with balanced precision movements expressing intense concentration and self-absorbtion. In its original rural form it is a dance performed in carnival by disguised characters, its name deriving from a fierce tribe in Asia Minor. Next most popular is the Khasapiko (meaning butcher’s dance) in slow 2/4 meter, danced by two or three men held by the shoulders and moving back and forth, usually close friends who have developed their own variations on the basic step. A similar dance in fast tempo and moving to the right is Serviko. P-oth dances were used as a base to create a new dance called Zorba dance or Syrtaki. This dance became very popular around the world in the Sixties and is still the highlight of Greek fraternity balls abroad and every tourist cabaret in Greece. Other rebetiko dances are Karsilama (i.e. face-to-face) with a 9/8 time signature, danced by couples, and the Tsifteteli (i.e. double-chord-strum), a solo dance in 4/4 resembling a subdued or mock belly dance.

The rebetika dancing style bears the mark of its urban origin. Suitable for dancing in the small space cleared by tables in tavernas, it is danced solo or by very few persons. Movements seem precise and calculated, the body crouches forward, arms outstretched to keep the balance. Originally practiced almost exclusively by men, it reflects the individualism of the towns-person, as opposed to the large circular dances stressing village communality, while village dancing is based on the repetition of the same steps over a very long time a dance might last half an hour or more – rebetika dances rely on the incessant variation of steps for the few minutes during which their songs last.

Until the Fifties middle-class Greeks and the media were contemptuous of rebetika music and dance. Then, composers Manos Hadjidakis (“Never on Sunday”) and Mikis Theodorakis(“Zorba the Greek”) started to compose music for films and popular songs adapting rebetika style to modern taste. They had immediate success in Greece and abroad, establishing a revival of the style although the original social conditions of its existence had disappeared. Now rebetika is widely adopted socially and is played in the radio and T.V. Most tavernas feature a modernized version of songs and dancing of this style. Young men and women dance it invariably, while patrons are encouraged to show their appreciation by breaking dishes on the dance floor.

4. Social Dance

After the War of Independence (1821-1827) the liberated Greek provinces founded an independent State; other provinces were attached to it one after another, until Greece reached its present boundaries a hundred years later. The first king came from Bavaria and his court introduced European couple dances to the new capital. Major Greek communities in the diaspora were already familiar with these dances and the Athenian middle class gradually adopted them. European fashion dances became the rule for home gatherings and celebrations in the towns, with an occasional Greek dance at the end. There are no ballrooms or competition dancing. Discotheques are very popular, there are more than one hundred in the greater Athens area, where more than a third of the population of the country lives.

In Athens, besides the taverns featuring rebetiko dance music, there are two dozen tavernas with folk musicians from particular regions (Crete, Epirus, Islands, Pontic, Thrace). There, patrons of country origin usually go with their families to meet fellow villagers who reside in Athens and to dance their own dances. Major towns in Macedonia have such tavernas with Pontic dance music, Cretan towns have tavernas with local music. In general, Greeks distinguish between bouzouki tavernas (with rebetiko music), clarinet tavernas (with traditional music from the mainland) and violin tavernas (with music from the islands and the coasts).

5. Theatrical Dance

Stage dancing was unknown in Greece during the Turkish occupation. By the middle of the 19th century touring foreign groups started giving performances in the capital of the new State. At the turn of the century several cafe-chantants in Athens offered cabaret shows that included dancing numbers, always by foreign artists. The “review” genre, featuring sketches of political satire and dancing is still very popular, with half a dozen theaters in Athens.

The first notable performance of Greek drama was given in the ancient theater of Delphi in 1927. It was organized by poet Angelos Sikelianos and his wife, American archaeologist Eva Palmer. Aeschylus’ “Prometheus Bound” was presented, the event was combined with a folk festival, exhibitions and lectures. The “Delphic Feasts” were repeated in 1930 with Aeschylus’ “Suppliants”, also choreographed by Eva Palmer, who was a friend and follower of Isodora Duncan. Duncan had given two performances in Athens in 1912 and had tried to establish a dance academy there.

In 1932, the National Theater – founded the same year in Athens – presented “Ajax”, establishing a tradition of commissioning dancers and choreographers to teach movement to the chorus of Greek plays. The chorus was composed of actors, rarely dancers, but some dance training has been part of the actors’ schools curriculum. Having practically no information on the movements of the chorus in ancient drama, choreographers’ approach to the modern presentations vary from rythmical recitation combined with a sequence of postures, to elaborate creations. Their main source of inspiration, though, remains thetraditional dancing of modern Greece. Already in the 1927 performance of “Prometheus” the chorus entered the scene singing and dancing a syrtos. After World War II interpretations by the National Theater, the Pireaus Theater of Dimitri Rondiris and the Art Theater of Karolos Koon have followed this line. The tendency was to move away from group recitation and archaic gestures, into singing and dancing as derived from the living popular tradition.

The “Lyrike Skene”, a State theater presenting opera and operetta, was founded in 1940 and included a small corps-de-ballet of trained dancers. Since 1960 it has been giving ballet evenings about twice a year. Another troupe was the “Greek Chorodrama” under the first dancer and choreographer Ms. Ralou Manou. Founded in 1952, it has employed the most well-known Greek composers, painters and choreographers in an effort to bring ballet closer to a home-grown inspiration. Other private initiatives are the “Experimental Ballet” under Mr. Yannis Metsis (since 1956), the “Sismani Ballet”, an offspring of the school of Ms. Iro Sismani (between 1955 and 1962), and more recently, the “Classical Ballet Center” under Ms. Rene Kammaer and Mr. Leonidas de Pian.

6. Dance Education

The first ballet school was founded in Athens by Mr. Morianoff in 1929. It was followed in 1930 by Ms. Koula Pratsika, whose school became the “State School of Dance Art” in 1972. Several other schools were also founded before the War. There are now 200 private dance schools in Greece, three fourths of them in Athens. The total number of their students is 11,000, most of them are in their teens and taking one and a half hour’s training three times a week. The predonimant course is rythmical movement, introduced in Greece by Marguerite Jordan as early as 1913 in the Conservatory of Music.

Ten schools, totalling 200 students, follow the 3-year, 20-hours a week curriculum prescribed by the Ministry of Culture, so they can present their graduates for the State examination. 20 to 25 students pass this examination every year, giving them the right to teach dance in private schools.

Dance is not taught in high schools or Universities. Some folk dances are taught in the Academy of Physical Education so that gymnastics teachers can teach them in high school, often with poor results. Private dance schools usually teach a few folk dances to their students.

L’étude

Le présent article est un compte rendu sur une enquête en cours depuis 1987 au sujet de la danse traditionnelle dans l’île grecque de Karpathos. L’étude repose sur une grande série d’interviews non directives, de préférence avec des personnes agées. Elle est complétée par la recherche bibliographique, l’observation participante, la comparaison avec les îles voisines et le filmage. Les données recueillies sont classées et analysées par village, par époque, par occasion de danse (mariage, baptême, fête patronale…), par tranche d’âge, sexe, occupation… La période de référence est celle entre les années ’30 et ’50, avant les distorsions dues aux contacts avec le monde extérieur.

Le but est de dégager des conclusions concernant d’une part la répartition géographique, chronologique et démographique des coutûmes de danse, et d’autre part (ce que je considère le plus important) d’élucider les rapports qui existent entre danse et société. Un livre est actuellement en préparation, un disque a déjà été publié.

Dans les études habituelles dans le domaine de la danse, le contenu moteur (le mouvement) est le sujet qui occupe la première – et trop souvent la seule – place. Dans le présent projet, par contre, l’accent est mis sur les aspects sociaux, la place qu’occupe la danse dans la vie du groupe social, les valeurs qui s’y rattachent, la parole qui entoure et qui pénètre la danse.

Je me limiterai ici à une tentative assez audacieuse : celle de rapprocher deux systèmes de nature très différente. D’un cotê, le rituel de la danse, et de l’autre cotê la stratification sociale et le système de transmission des biens par la dot.

Parmi la centaine d’îles grecques habitées, Karpathos est une des plus éloignées, se situant entre la Crète et Rhodes. Elle est aussi un des endroits où la vie traditionnelle a été le mieux conservée jusqu’à une époque récente; ceci pour plusieurs raisons: elle est loin des routes maritimes, elle possède peu de ressources naturelles et peu de sites qui se prêteraient au développement touristique.

Un autre facteur aussi important: Karpathos n’a été rattachée à l’Etat grec qu’en 1948. Depuis, la politique de nivellement culturel imposée par la capitale aux provinces, réussit à aplanir rapidement les spécificités locales. Récemment, la construction d’un aéroport et l’ouverture de routes vers les villages les plus éloignés annoncent l’invasion touristique qui se prépare.

C’est la raison pour laquelle cette étude a aussi le caractère d’une “fouille de sauvetage”, selon le terme qu’utilisent les archéologues quand ils interviennent sur un terrain avant la construction immobilière, pour emporter rapidement les vestiges dans les caves des musées.

Le système social

Commençons par le système social et après nous passerons au système de danse, afin de voir comment le deuxième reflète le premier. La danse du village est la mise en scène de la vie du village.

Karpathos était réputée une île prospère pendant l’Antiquité, mais dépuis les temps historiques elle a périclité. Son sol rocheux et aride, sa position géographique éloignée, les incendies et les séismes, les envahisseurs et les pirates ne pouvaient pas permettre un essor durable. Le caractère austère du paysage a marqué les habitants. Une petite société fermée, qui se reproduit dans les lieux d’immigration, qui ne fait jamais parler d’elle, sauf quand les reporters de la télévision veulent montrer des scènes de la vieille Grèce disparue.

L’île a une forme étroite et longue, sur laquelle sont répartis les dix villages. Le village principal, où se trouvent le port, l’aérodrome et les services administratifs, se situe à l’extrémité sud. Les routes ayant été tracées récemment, les villages ont toujours vécu dans un relatif isolement. Ainsi, aujourd’hui, plus on avance vers le nord, plus les villages ont gardé les vieilles coutumes, jusqu’à Elympos, le village le plus éloigné qui est le bastion des traditions.

Une particularité frappante parmi les coutumes est le système de la dot. C’est un système assez élaboré, dont voici les grandes lignes.

A l’occasion de son mariage, la fille aînée reçoit en dot tout le patrimoine de sa mère. Ses soeurs sont contraintes de travailler pour elle et de vivre chez elle jusqu’à leur propre mariage. Ses parents ont fait construire une maison pour elle ou, s’ils n’ont pas les moyens, ils se retirent ailleurs en lui laissant leur maison pour habiter avec son mari. Ainsi, une fille cadette ne reçoit pas de dot, à moins de porter le même prénom qu’une tante qui n’a pas d’enfants. Porter le nom de quelqu’un de la famille, c’est être son continuateur spirituel, donc aussi son héritier matériel.

Le patrimoine reçu par la fille aînée consiste généralement en une maison équipée, des champs de blé et des bêtes de somme, ainsi que de l’argent liquide sous forme de pièces d’or. Cet or, qui représente l’épargne des générations précédentes, elle le porte en collier sur sa poitrine, à la danse et à l’église. Elle ne se permettra jamais de vendre une de ces monnaies d’or; par contre, elle cherchera à rajouter des pièces avant de présenter le collier à sa fille aînée.

Par analogie, le fils ainé reçoit le patrimoine de son père, à la différence près qu’il n’a pas l’obligation de fournir la maison conjugale. Une fois marié, c’est lui qui est responsable de la gestion de tous les biens de la famille et, en cas de grande difficulté, il sera contraint de vendre ses propres biens pour couvrir ses besoins. Si le fils est enfant unique, sa mère ne lui donnera pas sa propre dot, elle la gardera en attendant de la donner directement à celle de ses petites filles qui portera son nom.

Ainsi, les biens se transmettent suivant deux lignes de filiation parallèles, la ligne des femmes étant la plus importante, puisque leurs biens ne peuvent que croître d’une génération à l’autre. C’est un système qui impose d’une part la concentration des fortunes et d’autre part leur immobilisation aux mains des femmes. Ceci est d’autant plus frappant que le système legal établi en Gréce prévoit la répartition équitable entre tous les enfants, ce qui a abouti au découpage des lots en parts infimes. Le droit coutumier de Karpathos vise par contre au maintien de quelques “grandes propriétés terriennes” au niveau du village, détenues par un petit nombre de femmes. Ce phénomène ne trouve pas d’analogie dans le reste de la Grèce.

Selon certains chercheurs, nous nous trouvons face aux vestiges d’une société matriarchale qui a survécu jusqu’à nos jours. Cette thèse est renforcée par les études linguistiques qui ont montré que le dialecte local est le plus proche du Dorien, de l’ethnie qui a précédé les Achaiens de la période classique. En tous cas, il est difficile pour la recherche historique d’aller plus loin, vu le manque de documents sur la société de l’île avant le 20ème siècle. Ajoutons aussi que leur musique est monophonique, d’un type pré-byzantin, malgré les influences du chant byzantin pratiqué dans l’eglise. Nous avons même découvert des traces d’une forme de polyphonie archaçque.

Passons maintenant à la fête et à la danse.

Le système de danse

La fête à Karpathos, que cela soit à l’occasion d’un mariage, d’un baptême ou le jour du saint patron d’une église, n’est pas radicalement différente dans son déroulement des fêtes qui ont lieu ailleurs en Grèce. Chaque petite région du pays a ses spécificités qui sont importantes, mais au fond on trouve toujours une trame commune. Le témoin d’une fête à Karpathos est frappé d’abord par la solennité de l’ambiance, et ensuite par la durée de la danse.

Les participants ne donnent pas une apparence particulièrement gaie; par moments, on se croirait à une messe. On ne retrouve pas les exclamations bruyantes des montagnards du continent, ni les coups de fusil en l’air des Crétois. Les femmes et les enfants, groupés sur un cΪté de la pièce, regardent silencieux. Les hommes, assis autour d’une grande table, chantent à tour de rΪle.

Autour d’eux, rasant les murs, les danseurs. Le regard vague, ils se tiennent serrés par les coudes dans une ronde ouverte qui avance lentement et qui ne se dissoudra qu’à la fin de la fête, des heures ou des jours plus tard. Le corps reste droit mais les pieds bougent sans arrêt sur un rythme rapide et syncopé. Le pas est toujours le même, fait presque sur place avec des flexions sur les pointes des pieds et sur les genoux. La danse est très difficile à exécuter par ceux qui ne sont pas du village, à cause de ce balancement irrégulier que tout le cercle exécute comme un seul corps.

Quand un danseur est fatigué après une ou plusieurs heures de danse continue, il va simplement s’asseoir, de même qu’à tout moment un danseur ou une danseuse peut entrer dans la ronde.

Ce sont les hommes qui commencent la danse. Au début de la fête, ils chantent des vieux chants à table. Les instruments qui les accompagnent sont la “lyra” (un violon primitif à 3 cordes), la “tsambouna” (une cornemuse sans bourdon) et le luth. Les musiciens s’alternent sans interrompre la mélodie. Après les chants, ceux qui sont à table passent aux vers improvisés: chacun à son tour compose, avec une facilité incroyable des couplets inspirés par l’occasion, souvent il y a ainsi entre les hommes des conversations entières rimées.

Puis, à un moment, quelques uns des hommes se lèvent et forment une petite ronde. C’est l’ouverture de la danse, danse très lente, presque un piétinement sur place qui s’appelle le “kato” (la “basse” danse). Plus tard, les jeunes femmes, l’une après l’autre, se joignent à la ronde. Chacune se met à la droite de l’homme qu’elle a choisi comme cavalier. Plusieurs danseuses peuvent choisir le même homme, elles sont souvent cinq ou plus à s’aligner à sa droite, mais seule la première est sa dame à proprement parler. Ainsi, un danseur avec ses danseuses constituent, selon eux, “une part de la ronde”.

Quand le cercle ouvert est garni, chacun des danseurs chante à son tour des vers improvisés louant sa dame. Puis le tempo devient rapide, c’est la danse qu’ils appellent “Pano” (“haute” danse). C’est cette danse qui occupe presque la totalité de la fête; quand ils parlent de danser, c’est à elle qu’ils pensent.

La ronde avance lentement vers la droite et la place du meneur est toujours tenue par un homme. Il est le seul à avoir ses dames à sa gauche et le seul autorisé à faire des figures. Ces figures ne sont pas des sauts impressionnants ni des frappés des pieds par terre que l’on observe dans d’autres régions grecques. Ce sont plutΪt des variations discrètes et fines sur le rythme, qui demandent une grande sensibilité et une maîtrise parfaite du style local.

Quand le meneur a visiblement montré ses capacités, le dernier de la chaîne se détache avec ses danseuses et vient prendre la première place. Ses danseuses sont venues à sa gauche, ainsi elles deviennent dames du danseur voisin puisque c’est lui qui les a maintenant à sa droite. De cette manière, tous les hommes passent par la place du meneur et chaque femme danse à cΪté de chacun des hommes à la longue.

Si un danseur s’absente pour boire un verre ou pour fumer une cigarette, la chaîne se referme derrière lui, mais sa place reste vacante jusqu’à son retour. De même, une danseuse peut partir pendant un long moment, mais il serait mal vu qu’elle revienne à une autre place de la chaîne.

J’ai présenté les éléments de base d’un système très élaboré. La description de l’ensemble des règles demanderait beaucoup plus de pages. Toutes ces règles sont implicites, les habitants du village trouvent une grande difficulté à les formuler lors des entretiens. Elles n’en sont pas moins strictes pour autant, toute infraction entraîne des réactions, qui sont de nature variable selon la situation.

Ainsi, après la formulation des règles de conduite de danse, l’objectif de l’étude est de trouver pour chacune d’elles la raison d’être, l’importance relative, les sanctions qu’entraîne son infraction, le mode de mémorisation et de transmission, enfin tout son fonctionnement dans la vie du village.

Dans une société traditionnelle, la parole est le véhicule privilégié, ainsi la parole de la danse donne au chercheur une richesse d’éléments complémentaires au contenu moteur.

Les rapports entre les deux sustèmes

Voyons maintenant comment les récits des habitants révélent des rapports entre le système de la dot et le système de la danse. Ceci, bien sûr, à l’état pur des deux systèmes.

1) Les deux voies de transmission du patrimoine (de mère en fille aînée et de père en fils aîné) font qu’au village il y a les biens qui appartiennent toujours aux hommes et ceux qui restent toujours aux mains des femmes.

De façon analogique, les hommes et les femmes se rendent à la danse séparemment. Il est rare qu’une famille entière aille en groupe à une fête patronale ou de noces. La mère s’y rend avec sa fille aînée, les autres filles restant à la maison tant que celle-ci n’est pas mariée. D’ailleurs, aussi bien la mère que la fille peuvent y être déjà allées pour assister dans les différentes phases des préparations. Le père passe peut-être d’abord par le café pour rencontrer ses homologues; là, ils attendent qu’un petit garçon vienne les appeller quand tout sera prêt. Les jeunes hommes, plus mobiles, iront à la fête par petits groupes, puis partiront et reviendront à plusieurs reprises.

Tout au long de la fête, comme souvent d’ailleurs dans la vie du village, les différents groupes d’âge et de statut agissent ensemble, comme un choeur de la dramaturgie antique.

2) Le statut social est particulièrement mis en évidence par le costume. Le costume traditionnel, à l’instar du costume moderne, illustre toute l’histoire personnelle de la personne. Dès le premier regard on sait s’il s’agit d’une jeune femme ou d’une femme mariée, veuve, épouse de fermier ou de berger, en deuil,…etc. De plus près, on distingue la qualité de la broderie, le choix des couleurs, le velours importé par un frère marin. On distingue encore les mille détails de l’habit qui représentent tant d’heures pour se vêtir et tant d’années de confection.

Pour les hommes, le costume est moins élaboré mais toujours riche en renseignements. De plus, une bonne récolte ou des moutons vendus se trahissent par plus de pièces jetées aux musiciens ou par une nouvelle piéce en or au collier de sa fille.

Ce collier, composé de pièces d’or qui couvrent parfois son buste jusqu’à la taille, produit lors de cette danse sautillée un bruit continu qui ne cesse de rappeller à tous non seulement le statut de fille aînée mais aussi de donner une mesure de la richesse de sa famille.

Ceci explique aussi le fait que l’aînée n’ait pas de place privilégiée dans la danse; une fois dans la ronde, elle a droit aux mêmes égards que les autres femmes.

3) Quand, au début de la danse, chacun des danseurs improvise à son tour des vers chantant les louanges de la danseuse qui est venue à sa droite, tout le monde a l’oreille tendue. Les danseurs répètent ces vers en choeur. Ce qui ne se voit et ne s’entend pas c’est que dans les jours qui suivent la mère de la jeune femme envoie un grand gâteau qu’elle a cuit, chez le danseur qui par ses distichs a fait gagner à sa fille quelques points dans la considération du village.

4) Les femmes mariées entrent rarement dans la ronde quand les jeunes femmes dansent. Récemment mariées, elles entrent à la demande du mari ou d’un frère. Mais plus les années passent, plus elles sont réticentes aux invitations. Elles disent que la priorité appartient aux plus jeunes qui doivent s’amuser tant qu’elles peuvent en même temps que se montrer pour trouver un mari. Plus tard, quand elles ont une fille à marier, elles ne dansent qu’en des circonstances exceptionnelles.

Par contre, les hommes dansent presqu’autant après le mariage qu’avant. Seulement, avec l’âge ils restent moins longtemps dans la ronde. On trouve des hommes qui sont peu attirés par la danse et d’autres qui dansent beaucoup pendant toute leur vie, tandis que les femmes dansent énormément avant le mariage, mais abandonnent rapidement après.

- Ϊles assignés à chacun des deux sexes. Aucune place n’est interchangeable. Par exemple, aucune femme n’accepterait de prendre la première place, ni la dernière place non plus. Ou encore, c’est la jeune femme qui en entrant dans la ronde a le choix de son partenaire.

Ce qui est à l’homme ne peut pas être à la femme, et inversement. La première place est à l’homme, mais aussi la dernière. Le choix du partenaire est à la jeune femme qui entre dans la ronde. Exceptionnellement, un homme peut inviter une femme très proche et entrer avec elle; sinon, une fois dans la ronde ce sont les dames qui le choisiront.

6) Mais, ce que l’on ne voit pas dans une scène de danse traditionnelle est beaucoup plus important que ce que l’on y voit. Prenons le cas de la mère qui accompagne sa fille à la danse et essayons de retracer sa démarche mentale telle qu’elle se révèle par les consultations.

Elle est assise, au départ, avec les autres femmes, sa fille à cΪté d’elle. La première chose qu’elle cherche est une “part de ronde” convenable pour sa fille. C’est que, en effet, elle ne peut pas envoyer sa fille n’importe où, la place choisie a une importance capitale. Il faut faire valoir la jeune fille au maximum, tout en minimisant les risques de ridicule ou de rejet. Pour cela, il faut prendre en compte plusieurs critères:

– Il vaut mieux être à cΪté de bons danseurs, sinon on est vite fatigué et on fait mauvaise figure.

– Il ne faut pas être dans la “part” d’un homme qui risque de provoquer des commentaires. Par exemple, si la fille va à cΪté d’un jeune homme, tout le monde va dire qu’elle le drague. De même que s’il s’agit d’un homme mûr mais qui a un fils à marier.

– Il ne faut pas non plus aller dans la part d’une famille avec laquelle on a des disputes.

– La jeune fille danse naturellement dans la “part de ronde” de son père ou d’un proche parent. Mais si cela se reproduit trop souvent, ceci risque d’être

interprêté comme un trop grand attachement à sa famille.

– D’autre part, la fille doit trouver un mari, et le meilleur mari possible. Ainsi, la place où elle ira se mettre constitue un geste à la fois assez voilé et perceptible par les autres femmes qui savent bien lire les signes. Par exemple, nous avons vu que la ronde, qui pour un observateur extérieur est un chaîne continue, représente pour quelqu’un du village une succession de groupes indépendants,

des “parts de ronde”. Ainsi, la danseuse qui prend place à gauche d’un danseur n’est pas sa dame, mais on sait qu’elle deviendra sa dame après un tour

- Ϊt près du candidat choisi.

7) Aussi, on doit respecter le statut social. Une fille aînée se doit d’épouser un fils aîné, sinon l’inégalité serait trop grande, et même de préférence le fils aîné d’une famille aussi importante que la sienne. D’autre part, pour une fille cadette de fermier, il est préférable d’épouser un jeune homme d’une famille de bergers (les fermiers ont toujours besoin des bergers, leurs produits sont complémentaires).

Et pour terminer, c’est encore la parole, la parole chantée. Pour montrer une fois de plus les liens inséparables entre parole et mouvement: Si on ne respecte pas les règles du système de danse, c’est le système social qui va intervenir. Le premier danseur de la ronde, et parfois même un autre danseur, va composer instantanément des vers de sa réaction. La parole chantée échappe aux contraintes de la parole ordinaire. Voilà le couplet qu’a lancé une jeune femme cadette qui s’est sentie refoulée par une aînée:

Viens à la danse, que les gens puissent te mesurer,

et laisse de coté ta fortune en champs de blé.

Alkis Raftis

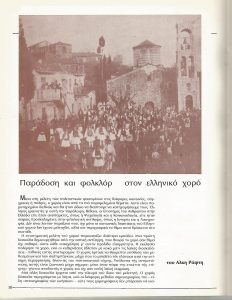

Για μια φυσική μουσικοχορευτική διατροφή, Φυσική διατροφή, 12.

Αθήνα, 11/1989, σελ. 65-67. Δημοσίευση στο περιοδικό Παράδοση και Τέχνη 027, σελ. 18-19, Αθήνα, Δ.Ο.Λ.Τ., Μάϊος-Ιούνιος 1996.

Για μια φυσική μουσικοχορευτική διατροφή

Αλκης Ράφτης

Είναι πολύ ευχάριστο να βλέπει κανείς να φουντώνει το κίνημα για τη φυσική διατροφή στην Ελλάδα. Δεκάδες χιλιάδες άνθρωποι αντιλαμβάνονται ότι οι επεξεργασμένες τροφές που προσφέρονται από την βιομηχανία και που διαφημίζονται κατά κόρον περιέχουν βλαβερά πρόσθετα συστατικά, ενώ στερούνται πολυτίμων θρεπτικών ουσιών. Αυτό όμως που δεν έχει αντιληφθεί ακόμα το κοινό, ούτε όμως και οι οπαδοί της φυσικής διατροφής, είναι ότι κάτι ανάλογο συμβαίνει με την πολιτιστική μας διατροφή.

Οι βιομηχανίες του θεάματος έχουν κατακλύσει την αγορά με ανθυγιεινά πολιτιστικά προϊόντα που δηλητηριάζουν τα γούστα μας χωρίς να το καταλαβαίνουμε. Η μουσική, το τραγούδι και ο χορός που μάς τριγυρίζουν δεν είναι παρά συνθετικά προϊόντα γεμάτα χημικές ουσίες, κατασκευασμένα μέσα σε εργοστάσια-στούντιο, από ανθρώπους που δεν σκέφτονται παρά το εύκολο κέρδος. Ανάμεσα στην τροφή για το στομάχι, και στην τροφή για τα αυτιά ή τα μάτια, η αναλογία είναι εμφανής. Η μόνη διαφορά είναι ότι για το στομάχι βρέθηκαν επιτέλους αρκετοί άνθρωποι να ενδιαφερθούν, ενώ για την μουσικοχορευτική διατροφή κανένας.

Οπως η διαφήμιση έπεισε τον κόσμο ότι το άσπρο και αφράτο ψωμί είναι πιο καλό, έτσι κι οι εταιρείες δίσκων μάς έχουν πείσει ότι τα τραγούδια της κάθε χρονιάς είναι καλύτερα από της προηγούμενης. Ξεχάσαμε ότι για το καλό ψωμί υπάρχει ένα αλάνθαστο κριτήριο ποιότητας: η διάρκεια. Το χωριάτικο ψωμί που έπλαθε η γιαγιά μας κρατούσε εβδομάδες, ενώ το σημερινό ψωμί τού φούρναρη δεν τρώγεται μετά από δύο μέρες. Τα τραγούδια που μάς σερβίρουν σήμερα κρατάνε με τη βία λίγους μήνες, ενώ τα παλιά τραγούδια κρατούσαν δεκαετίες. Τα τραγούδια που τραγουδούσε ακόμα η γιαγιά μας είχαν κρατήσει αιώνες, γιατί ήταν ζυμωμένα με φυσικά υλικά.

Ποιά ήταν τα φυσικά υλικά που τροφοδοτούσαν την διασκέδαση των ανθρώπων πριν εισβάλει η βιομηχανική παραγωγή; Θα δώσουμε παρακάτω μερικά παραδείγματα, ο καθένας όμως μπορεί να βρει ανάλογες περιπτώσεις από την δική του εμπειρία, αρκεί να ευαισθητοποιηθεί στο πρόβλημα. Οπως δεν χρειάζεται να είναι κανείς διαιτολόγος για να προσέχει τι τρώει, έτσι δεν χρειάζεται να σπουδάσει Μουσικολογία για να προσέχει τι ακούει από το ραδιόφωνο.

Η παλιά μουσική (τα γνήσια δημοτικά τραγούδια, όπως και η βυζαντινή υμνωδία) ακολουθεί την φυσική κλίμακα, ενώ η μοντέρνα μουσική (κλασική και ελαφρά) είναι γραμμένη πάνω στην συγκερασμένη κλίμακα. Δεν είναι τυχαίο ότι ονομάζεται “φυσική κλίμακα”, γιατί είναι η κλίμακα που βγαίνει με “φυσικό” τρόπο. Οταν πάρετε ένα κομμάτι καλάμι και τού ανοίξετε τρύπες για τα δάχτυλα όπως απλά κάνει ένας βοσκός, τότε παίζετε στην φυσική κλίμακα. Η κλίμακα, δηλαδή η σειρά από νότες, είναι το θεμέλιο πάνω στο οποίο χτίζεται οποιαδήποτε μελωδία. Σήμερα, το αυτί μας έχει ξεχάσει αυτή την κλίμακα, αφού έχει βομβαρδιστεί μια ζωή από “έντεχνη” μουσική.

Ο σύγχρονος χορός είναι μια ανάλογη περίπτωση. Ξεκομμένος από τις ρίζες του, εμπλουτισμένος με αφύσικες κινήσεις, θεαματικός και όχι λειτουργικός, μπορεί να χορευτεί μόνο από ειδικά εκπαιδευμένους επαγγελματίες. Ο μέσος άνθρωπος σήμερα συνήθισε να βλέπει αδιάφορα κάποιο χορευτικό θέαμα στην τηλεόραση, αλλά ξεσυνήθισε να διασκεδάζει χορεύοντας ο ίδιος. Οταν τον βαραίνει ένας καημός δεν μπορεί πια όπως ο Ζορμπάς – που κι αυτός κακοποιήθηκε με το Συρτάκι – να σηκωθεί με απλωμένα τα χέρια του και να ξεδώσει.

Ο φυσικός χορός, ο παραδοσιακός, παρουσιάζεται διαστρεβλωμένος στην τηλεόραση και στα φεστιβάλ από συγκροτήματα της δεκάρας. Παρεξηγημένος και γελοιοποιημένος, ο παραδοσιακός χορός κινδυνεύει να γίνει κάποτε γυμναστική για τα παιδάκια. Ενώ θα μπορούσε να συνεχίσει να είναι κτήμα και μέσο έκφρασης όλου του κόσμου.

Προσέξτε πώς παίζουν οι μουσικοί που ακούμε καθημερινά: γρήγορα (για να μην φαίνονται οι τεχνικές ατέλειες), δυνατά (για να κρύβεται το φτωχό ηχόχρωμα), χωρίς αυτοσχεδιαστική εισαγωγή (όπου φαίνεται η ατομική δημιουργία), με πολλά όργανα συγχρόνως (το ένα σκεπάζει το άλλο και μπερδεύεται ο ακροατής), κομμάτια διαρκείας λίγων λεπτών (έτσι δεν προλαβαίνεις να καταλάβεις την γύμνια της μελωδίας). Ακριβώς το αντίθετο από ό,τι έπαιζαν οι παραδοσιακοί μουσικοί: λίγα όργανα στη ζυγιά ή την κομπανία, καταγόμενοι από το ίδιο σόι ή το ίδιο χωριό, έπαιζαν μια ζωή μαζί στα γλέντια και στα πανηγύρια. Οχι όπως τώρα που οι μουσικοί γνωρίζονται λίγες μέρες πριν πιάσουν δουλειά.

Ο παραδοσιακός οργανοπαίχτης άρχιζε το κάθε κομμάτι με ένα ταξίμι, μια εισαγωγή όπου ξεκινάει από μακριά και πλησιάζει σιγά-σιγά την βασική μελωδία, κεντώντας πάνω σε ελεύθερο ρυθμό. Ζητήστε τώρα από έναν ελαφρό λαϊκό μουσικό να αυτοσχεδιάσει χωρίς το μονότονο χτύπημα της συνοδείας, και θα πανικοβληθεί. Οι παππούδες μας άκουγαν με τις ώρες τις αργές μελωδίες τους, ακριβώς όπως μασούσαν καλά την κάθε μπουκιά φαγητού για να πάρουν τις ουσίες και να την χωνέψουν καλύτερα. Σήμερα, οι ντισκοτέκ και τα νυχτερινά κέντρα είναι τα φαστφουντάδικα της μουσικοχορευτικής μας διατροφής.

Οι παλιοί, όταν μετά από ώρα είχαν μπει καλά στο νόημα του κομματιού, σηκώνονταν να χορέψουν. Αργά, συλλογικά, χωρίς προσχεδιασμένες φιγούρες, με βήματα ζυγισμένα, οι χορευτές επικοινωνούσαν μεταξύ τους και με τα όργανα. Τον παραδοσιακό οργανοπαίχτη τον πλήρωνες όσο ήθελες εσύ, ανάλογα με το πόσο κατάφερνε να σε αγγίξει με το παίξιμό του. Η μουσική δεν περιεχόταν στην τιμή της μπριζόλας. Ούτε ήταν τσάμπα μουσική, παιγμένη από το ραδιόφωνο για να γεμίσει τις ώρες του προγράμματος. Ηταν μουσική στην ώρα της, διαφορετική για την κάθε στιγμή της ημέρας ή του χρόνου, προσαρμοσμένη στο περιβάλλον και στην ατμόσφαιρα, για ανθρώπους που γνωρίζουν προσωπικά τους οργανοπαίχτες και έχουν μάθει από χρόνια να γλεντάνε μαζί τους.

Η βιομηχανία του θεάματος είναι παντοδύναμη και μπορεί να μάς πλασάρει για μεγάλες επιτυχίες τα πιο ψεύτικα μουσικοχορευτικά προϊόντα. Ας μην γελιόμαστε, ακόμα και το πιο απλό τραγουδάκι δεν είναι αθώο. Οπως το απλό ρύζι που τρώμε είναι αποφλοιωμένο, χωρίς τις βιταμίνες του, λευκασμένο με χημικές ουσίες, γεμάτο ίχνη φυτοφαρμάκων. Τα λόγια είναι γραμμένα στο πόδι από κάποιον στιχουργό, η μελωδία φτιαγμένη πρόχειρα στα μέτρα μιας τραγουδίστριας που δεν έχει φωνή αλλά παρουσιαστικό, όλα παιγμένα βιαστικά γιατί η ώρα του στούντιο στοιχίζει πανάκριβα. Αν δεν βγαίνει κάτι καλό δεν πειράζει, ο δίσκος πρέπει να έχει δώδεκα κομμάτια, ούτε λιγότερα ούτε περισσότερα, και να βγει γρήγορα γιατί δεν έχουν οι πλασιέ της εταιρείας εμπόρευμα να δώσουν στα δισκάδικα.

Ετσι μπαίνουν μέσα στο προϊόν τα συντηρητικά (ηχητικά εφφέ, πλέι-μπακ, χορωδίες), οι χρωστικές ουσίες (φωτογραφίες, αφίσες, φωτεινές επιγραφές), οι ορμόνες (ερωτικές περιπέτειες του τραγουδιστή), η χοληστερίνη (ηλεκτρονικά όργανα). Τι σημασία έχει αν το τραγουδάκι έχει μειωμένη καλλιτεχνική θρεπτική αξία. Με την κατάλληλη συσκευασία (δίσκοι, εκπομπές, κέντρα, συναυλίες) και την έντονη διαφήμιση, κατάφεραν να δημιουργήσουν ένα καταναλωτικό κοινό λαίμαργο, παμφάγο, που μασουλάει παθητικά τα άμορφα μουσικά κομμάτια σαν τσίχλες οδηγώντας το αυτοκίνητο.

Το κακό τελικά είναι ότι δεν έχουμε μάθει να τρώμε, η μάνα μας επέμενε απλώς να αδειάζουμε το πιάτο. Εκείνη την εποχή όμως ό,τι και να έτρωγες δεν έκανε κακό. Tώρα όμως το σουπερμάρκετ είναι γεμάτο προϊόντα που πριν τα βάλεις στο στόμα σου θα πρέπει να διαβάσεις την ετικέτα και να αναλογιστείς τις παρενέργειες του κάθε παράξενου συστατικού τους. Μήπως θα πρέπει να γράφεται υποχρεωτικά σε ορισμένα τηλεοπτικά προγράμματα και δίσκους “Το Υπουργείο Πολιτισμού προειδοποιεί: Το άκουσμα βλάπτει σοβαρά το γούστο σας”;

Ενα τέτοιο κήρυγμα έκαναν η Δόρα Στράτου και ο Σίμων Καράς, δίνοντας έμπρακτα το παράδειγμα στις νησίδες που δημιούργησαν. Εμειναν όμως μέχρι σήμερα ξεχασμένοι ναυαγοί πάνω στις νησίδες αυτές ενώ τριγύρω συνεχίζεται ο τυφώνας της φτηνής εμπορευματοποίησης.

Δεν είναι εύκολο, ούτε σκόπιμο, να δίνουμε έτοιμες συνταγές. Την σωστή διατροφή, αυτήν που ταιριάζει στον οργανισμό του, θα την βρεί ο καθένας ψάχνοντας μόνος του. Φτάνει βέβαια να θέλει πραγματικά να ψάξει. Ας ελπίσουμε λοιπόν πως κάποτε θα στραφούν αρκετοί άνθρωποι προς την φυσική, την παραδοσιακή μουσικοχορευτική διατροφή.

Αλκης Ράφτης

Αλκης Ράφτης

Το σώμα, φορέας της κοινωνικής ιστορίας. Ο ελληνικός χορός

Χορός, Τεύχος 12, σελ.36-42, Καλοκαίρι 1990.

Ανακοίνωση στο 6ο συνέδριο της Α.S.F.Ε.C., Grenoble, 1983

Ο χορός κλείνει μέσα του την ιστορία της κοινωνίας στην οποία ανήκει.’Οπως η γλώσσα, η μουσική, η φορεσιά, ή οποιοδήποτε άλλο πολιτιστικό στοιχείο, έτσι και η γλώσσα των κινήσεων —που ο χορός αποτελεί την ποιητική της έκφραση— συνυπάρχει σε μια σχέση διαρκούς αλληλεπίδρασης με όλα τα υπόλοιπα στοιχεία του πολιτισμού κι ακολουθεί στενά την εξέλιξη του διαμέσου της ιστορίας του κοινωνικού συνόλου.

Ο παραλληλισμός με τη γλώσσα, στο μέτρο που η ομιλούμενη γλώσσα είναι ένα προνομιούχο μέσο έκφρασης κι επικοινωνίας, είναι ιδιαίτερα χρήσιμος. Οι άνθρωποι των γραμμάτων μελετούν εδώ κι αιώνες την καταγωγή και τις έννοιες των όρων του λεξιλογίου μας, τη γραμματική και το συντακτικό τους. Για το χορό όμως δεν έχει γίνει τίποτε ανάλογο. Πιθανόν η απουσία ενός τρόπου γραφής των κινήσεων του σώματος, μαζί βέβαια και με άλλους λόγους, έχουν συμβάλει στο να μη γνωρίζουμε από που προέρχονται οι κινήσεις μας, ποιο είναι το συγκεκριμένο νόημα τους, ποιοι είναι οι νόμοι που τις διέπουν.

Θα μπορούσαμε όμως να φανταστούμε ένα λεξικό κινήσεων για κάθε λαό. Ενα «λεξικό κινήσεων των Γάλλων» θα μπορούσε για παράδειγμα να καθορίζει πως η τάδε χειρονομία είναι γερμανικής προέλευσης, ενώ η δείνα αγγλοσαξωνικής κι ότι η άλφα κίνηση δηλώνει πόνο, ενώ η βήτα έκπληξη. Ετσι το νόημα μιας κλωτσιάς είναι αρκετά ξεκάθαρο, αλλά υπάρχουν διαφορετικοί τρόποι εκτέλεσης του ανάλογα με τις χώρες, ακόμη και οι ποδοσφαιριστές έχουν αναπτύξει μια μεγάλη ποικιλία γύρω απ’ αυτό.

Μπορούμε να πούμε πως υπάρχει μια ολόκληρη «γλώσσα κινήσεων», που γίνεται με την πρώτη αντιληπτή σ’ έναν ξένο που επισκέπτεται μια χώρα, αλλά ταυτόχρονα υπάρχουν κι ένα πλήθος «τοπικές διάλεκτοι κινήσεων», που διαφέρουν από περιοχή σε περιοχή, από χωριό σε χωριό ή ακόμη κι από οικογένεια σε οικογένεια. Μαθαίνουμε να χειρονομούμε, να γελούμε, να παίρνουμε στάσεις, να τρέχουμε, να θερίζουμε μιμούμενοι αυτούς που μας περιστοιχίζουν. Αυτό δεν σημαίνει ότι οι κινήσεις μας δεν έχουν ένα ξεχωριστό προσωπικό χαρακτήρα, όπως άλλωστε συμβαίνει και με την ομιλία μας που δεν είναι ποτέ ίδια με ενός άλλου, αλλά ότι το κοινωνικό σύνολο μας επιβάλλει το στυλ και τα όρια.

Ολα τούτα όμως δεν τα συνειδητοποιούμε στην καθημερινή μας ζωή γιατί ζούμε σε μια σύγχρονη, βιομηχανοποιημένη, αλλά κυρίως εγγράμματη κοινωνία. Αυτό μας οδηγεί σε μια πολύ σημαντική παρατήρηση: ότι από τη στιγμή που μια κοινωνία εναλφαβητίζεται (πολύ περισσότερο δε αν επιπλέον εκβιομηχανίζεται), όλη η κινησιολογία της υφίσταται μια μετατόπιση, ένα γρήγορο υποβιβασμό. Ο χορός, σαν κομμάτι της κινησιολογίας, υφίσταται κι αυτός μια ανάλογη παραμόρφωση.

Ο χορός, που έχει παραμεριστεί πια από τη σκηνή των σπουδαίων συμβάντων της δημόσιας ζωής, έχει βρει σήμερα καταφύγιο στην τηλεόραση και στις ντισκοτέκ’ αντί να είναι κτήμα του καθενός, έχει περάσει σχεδόν αποκλειστικά στα χέρια των επαγγελματιών. Ακόμη κι όταν καταφέρνουμε να χορέψουμε (μετά από παρακολούθηση μαθημάτων) ο χορός μας είναι άχρωμος, α-τοπικός, όπως ο τρόπος επικοινωνίας μας, αδύναμος να καταδείξει την καταγωγή μας ή να αφήσει να διαφανεί το κοινωνικό μας παρελθόν.

Η μελέτη του δημοτικού χορού σε μια χώρα σαν την Ελλάδα, όπου ο εκσυγχρονισμός δεν έχει ακόμη σβήσει τα τελευταία ίχνη αυτής της ιδιαίτερης σωματικής ομιλίας, παίρνει μια πολλαπλή σημασία: Πρώτα γιατί η παρατήρηση ανθρώπων από διαφορετικές περιοχές την ώρα που χορεύουν οδηγεί στη θεαματική επιβεβαίωση της ύπαρξης διαφορετικής χορευτικής διαλέκτου κατά περιοχή. Προσοχή: δεν πρόκειται απλά για διαφορετικούς χορούς από τη μια περιοχή στην άλλη (πράγμα που θα ήταν άλλωστε προφανές), αλλά για έναν τελείως χαρακτηριστικό κι ανεξίτηλο τρόπο που διακρίνει τους ανθρώπους κάθε περιοχής και τους προδίδει μόλις χορέψουν τους χορούς μιας άλλης. Αυτό είναι μάλιστα τόσο πρόδηλο, ώστε στα εθνικά θέατρα φολκλορικών χορών οι χοροί ορισμένων περιοχών με πολύ ιδιαίτερο, τοπικό χρώμα χορεύονται αποκλειστικά από νεαρούς χορευτές που κατάγονται από αυτές.

Επειτα, τα χορευτικά έθιμα της αγροτικής Ελλάδας σκιαγραφούν θαυμάσια τις κοινωνικές λειτουργίες του χορού. Οι εθνογραφικές έρευνες έχουν στρέψει μέχρι σήμερα ελάχιστα την προσοχή τους στους χορούς χωρών ήδη μελετημένων. Στην πλειοψηφία τους καταπιάνονται με χορούς πρωτόγονων κι απομακρυσμένων κοινωνιών. Αν όμως αντίθετα μελετούσαν τους ζωντανούς ακόμη χορούς μιας ευρωπαϊκής χώρας, που εξακολουθούν να συνδέονται με την καθημερινή της ζωή, θα επωφελούνταν από ένα πλήθος πολυτιμότατων και διεισδυτικών παρατηρήσεων.

Οι έρευνες μας συνίστανται στο να διαχωρίσουμε μέσα από την πρακτική του σημερινού χορού όσα στοιχεία ανήκουν στον τρόπο της ζωής του παρελθόντος.

Ο τελευταίος, που έχει αρχίσει πια να εξαφανίζεται και μάλιστα με γρήγορο ρυθμό, διατηρείται μόνο στη μνήμη όσων έχουν ζήσει στο χωριό πριν τον Πόλεμο. Η παρατήρηση των σημερινών πρακτικών παρουσιάζει ένα ανακάτεμα στοιχείων που θα προσπαθήσουμε να ξεδιαλύνουμε — συνδυάζοντας τα με τις διηγήσεις των παλιών —προκειμένου να εντοπίσουμε το πώς ήταν η κατάσταση του χορού σ’ ένα όχι και τόσο μακρινό παρελθόν, ας πούμε γύρω στα πενήντα χρόνια πριν. ‘Ενα παρελθόν σχετικά πρόσφατο, αλλά τελείως διαφορετικό αφού ανήκε σε μια ριζικά διαφορετική κοινωνία. Ετσι, το θέμα της μελέτης μας στρέφεται γύρω από μια κοινωνία που έχει επιβιώσει στις μέρες μας μόνο μέσα από τα διασκορπισμένα πια κομμάτια της, την ελληνική αγροτική κοινωνία, πριν από τη μαζική της επαφή με τον κόσμο των πόλεων.

Ιστορικοί και γεωγραφικοί λόγοι συνέβαλαν στο να ζήσουν για αιώνες οι κοινότητες των ελληνικών χωριών μέσα σε μια απομόνωση αυτάρκειας που επέτρεψε μια πολύ αργή εξέλιξη των πολιτιστικών χαρακτηριστικών τους. Η γλώσσα, η μουσική, η φορεσιά, τα έθιμα, προέρχονται όλα από την αρχαιότητα, ακολουθώντας μια αδιάκοπη γραμμή. Αυτή η διαπίστωση προκαλεί έκπληξη όταν γνωρίζει κανείς την πολυτάραχη ιστορία της χώρας. Εξηγείται όμως από την καταπληκτική επιμονή της ελληνικής κολτούρας (που εκδηλώνεται και στο χορό, όπως θα δούμε) καθώς κι από τη γεωγραφική της διαμόρφωση. Η μεγάλη ποικιλία των εδαφών της επέτρεπε στους κατοίκους να μετακινούνται λίγο πριν από κάθε αναμενόμενη επιδρομή κι αργότερα, μετά το πέρασμα των εχθρών να επανεγκαθίστανται στον τόπο τους.

Μετά τον τελευταίο πόλεμο, όταν ανοίχτηκαν δρόμοι που έφταναν μέχρι και σε χωριά τελείως απομακρυσμένα, όπου πριν χρειαζόταν κανείς ώρες με το μουλάρι για να φτάσει, όταν το ραδιόφωνο άρχισε να μεταδίδει τη φωνή της πρωτεύουσας κι όταν οι νέοι άρχισαν να φεύγουν για να δουλέψουν στις πόλεις ή στο εξωτερικό, τότε ήταν που ο τρόπος ζωής άλλαξε ριζικά. Αυτή όλη η παραδοσιακή κουλτούρα υπέστη, πριν ακόμη τον ολοκληρωτικό της μαρασμό, μια συστηματική δυσφήμηση από το μέρος της κυβέρνησης και του αστικού πληθυσμού. Απο την ίδρυση του σύγχρονου Ελληνικού Κράτους, εδώ και 150 χρόνια, όλες οι κυβερνήσεις συνέδεσαν την υλική πρόοδο με τη μίμηση των δυτικοευρωπαϊκών προτύπων. Η μικρή, τοπική μπουρζουαζία κατέληξε να πιστεύει πως η παραδοσιακή κουλτούρα ήταν συνώνυμη της οπισθοδρόμησης, της μιζέριας και της χοντροκοπιάς. Η εκπαίδευση στράφηκε ακόμη μια φορά προς την αραχαιολατρεία, την εξιδανίκευση του μακρινού παρελθόντος, αποκρύπτοντας τις πρόσφατες συλλογικές μας αξίες.

Ας διατυπώσουμε ένα πρώτο αξίωμα: ο χορός αποτελεί μια διπλή έκφραση που πρέπει κανείς να εξετάζει αδιάσπαστα, έκφραση του εσωτερικού και του εξωτερικού κόσμου ταυτόχρονα. Η έκφραση που πηγάζει μέσα από το χορευτή εκπροσωπεί τον ίδιο: την προσωπικότητα, το ατομικό παρελθόν, την ψυχική του κατάσταση τη στιγμή που χορεύει. Εκείνη πάλι που προέρχεται από το περιβάλλον του είναι αυτή που ο περίγυρος του επιβάλλει και διαφαίνεται αναπόφευκτα μέσα από το χορό του: η μουσική που ακούει, οι άνθρωποι που χορεύουν μαζί του ή τον κοιτάζουν, η ευκαιρία με την οποία χορεύει, ολόκληρο το παρελθόν της κοινωνικής ομάδας όπου ανήκει. Οπως είναι φυσικό, υπάρχει μια διαρκής αλληλεπίδραση μεταξύ αυτών των δύο πραγματικοτήτων, δεν πρέπει όμως να συγχέεται ο ρόλος τους.

Οι περισσότεροι ελληνικοί χοροί χορεύονται σε ανοιχτό κύκλο, πράγμα που δίνει την πρωτοκαθεδρία σ’ αυτόν που σέρνει το χορό. Αυτός διαλέγει το τραγούδι που θα χορευτεί και το παραγγέλνει στους μουσικούς, αυτός πάλι ελέγχει την κίνηση του κύκλου κι είναι ο μόνος που έχει το ελεύθερο να κάνει τις φιγούρες που θέλει. Ο χορός του ανήκει, κατέχει την τιμητική θέση κι όλα τα μάτια είναι καρφωμένα πάνω του. Οι υπόλοιποι χορευτές του κύκλου κάνουν τα βασικά βήματα, που μπορεί να είναι κι επιτόπου, καμιά φορά μάλιστα δεν κινούνται καθόλου, όπως γίνεται με τον Τσάμικο. Βρίσκονται εκεί για να συνοδεύουν μάλλον τον πρώτο χορευτή, για να δείχνουν ότι είναι στο πλευρό του, διαθέσιμοι την οποιαδήποτε στιγμή. Είναι συχνά τα ίδια τα μέλη της οικογένειας του ή οι φίλοι του.

Ο πρωτοχορευτής έχει τον πρωταγωνιστικό ρόλο, που είναι μεν ο πιο προνομιούχος, αλλά και ο πιο δύσκολος για να τον κρατήσει. Εκεί επάνω είναι ακριβώς που παίρνει την προτεραιότητα η εσωτερική έκφραση· προχωρεί πρώτος απ’ όλους ξεδιπλώνοντας την προσωπικότητα του. Η επιλογή της μουσικής, τα λόγια του τραγουδιού —πάνω στα οποία συχνά αυτοσχεδιάζει όταν το φέρνει η στιγμή— και οι παραμικρές κινήσεις του, αποτελούν δείγματα της προσωπικότητας του που όλοι παρατηρούν προσεκτικά προκειμένου να τον κρίνουν. Ο ελληνικός χορός σε ανοιχτό κύκλο μπορεί να μοιάζει ομαδικός με την πρώτη ματιά, αλλά στο βάθος δεν είναι τίποτε άλλο από το μοναχικό χορό του μπροστάρη. Δεν πρέπει προπαντός να τον συγχέουμε με τον τρόπο που χορεύουν τα φολκλορικά γκρουπ που δίνουν στις μέρες μας παραστάσεις, όπου όλοι οι χορευτές εκτελούν ταυτόχρονα τη μια μετά την άλλη διάφορες φιγούρες.

Ας μην ξεχνούμε ότι στα χωριά η κάθε οικογένεια είναι σχετικά απομονωμένη στην καθημερινή της ζωή. Οι άντρες συναντιούνται τα απογεύματα στο καφενείο, ενώ οι γυναίκες μαζεύονται τα πρωινά μ’ άλλες γειτόνισσες στις πίσω αυλές. Το κορίτσι δεν βγαίνει από το σπίτι πριν παντρευτεί παρά για να πάει στην πηγή τα ξημερώματα να φέρει νερό ή στα χωράφια μαζί με τους γονείς του. Την ημέρα που θα παρουσιαστεί σε έναν επίσημο χορό του χωριού, σημαίνει ότι είναι πια σε ηλικία γάμου. Τότε θα σύρει το χορό με τη σειρά της και θα τραγουδήσει μερικούς στίχους δικής της έμπνευσης, θα φέρει έτσι μία-δύο βόλτες πριν ξανασμίξει με την τελευταία του κύκλου για να δώσει τη θέση της στην επόμενη. Η φορεσιά της, φροντισμένη και κεντημένη από την ίδια, τα δίστιχα της, γεμάτα αλληγορίες και υπαινιγμούς, το κορμί και οι κινήσεις της θ’ αποτελέσουν αντικείμενο πολλών συζητήσεων για εβδομάδες μετά την πρώτη της εμφάνιση.

Ετσι σ’ έναν ελληνικό χορευτικό κύκλο, ακόμη κι όταν όλοι οι χορευτές κάνουν τα ίδια ακριβώς βήματα, δεν χορεύουν ωστόσο το ίδιο πράγμα. Ο μπροστάρης εκφράζει την ατομικότητα του κι οι υπόλοιποι το συλλογικό πνεύμα. Ο δημοτικός χορός είναι μια σκηνοθεσία μ’ ένα μοναδικό πρωταγωνιστή και τους κομπάρσους του. Ενας πετυχημένος χορός σύρεται από κάποιο «χαρισματικό» μπροστάρη, ενώ οι χορευτές που τον συνοδεύουν εκφράζουν μια όσο το δυνατόν μεγαλύτερη ομοιογένεια. Τα βήματα είναι απλά και ζυγισμένα, το θέαμα γίνεται τόσο ωραιότερο όσο τα σώματα των χορευτών χορεύουν πιο εναρμονισμένα, τόσο που να νομίζει κανείς ότι βλέπει ένα μόνο χορευτή.

Ο μπροστάσρης «κεντά» τις φιγούρες του σ’ έναν ήδη δοσμένο «καμβά» από κινήσεις, αυτόν που κρατούν οι άλλοι χορευτές. Μπορεί να κάνει παραλλαγές του βασικού βήματος, να χτυπήσει τα πόδια ή να πηδήξει, να κάνει μια στροφή επιτόπου ή να λυγίσει τα γόνατα του, ακόμη και ν’ αφήσει το αριστερό του χέρι από τον δεύτερο του χορού για να κάνει μερικά βήματα στο εσωτερικό του κύκλου κι ύστερα να ξαναγυρίσει στη θέση του. Οσο περισσότερο θέλει να κάνει φιγούρες, τόσο περισσότερο χρειάζεται έναν καλό δεύτερο, που να μπορεί να κρατάει σταθερό το χέρι του σαν στήριγμα και να διατηρεί ανεπηρέαστο το βήμα του απ’ οποιουσδήποτε αυτοσχεδιασμούς ή παραλλαγές του πρώτου. Ενας καλός μπροστάρης μένει πολλές φορές κι ακίνητος για μια στιγμή κι έπειτα ξαναπιάνει το βήμα ή παρεκκλίνει ελαφρά απ’ το ρυθμό, μένοντας λίγο πίσω ή προχωρώντας λίγο μπροστά από τη μουσική.

Ο μπροστάρης αυτό που δείχνει πρώτα απ’ όλα με τις φιγούρες του είναι η σωματική του ικανότητα, μια απ’ τις πιο σπουδαίες αρετές για ένα χωρικό. Η ευρωστία παίζει πρωτεύοντα ρόλο σ’ ένα περιβάλλον όπου δεν είναι δυνατόν να επιζήσει κανείς χωρίς να δουλεύει σκληρά, κι αποτελεί ένα προσόν που μπορεί να φανεί με το χορό. Παράλληλα ακολουθεί το ρυθμό προσπαθώντας ταυτόχρονα να τον παραβεί, να παρεκκλίνει από το μέτρο που του δίνει το νταούλι. Ο πόθος για προσωπική ελευθερία εναλλάσσεται με την ανάγκη κοινωνικής ενσωμάτωσης.

Τα χέρια δεν κινούνται πολύ, το σώμα μένει ευθυτενές και η έκφραση του προσώπου διατηρείται ήρεμη. Δεν χορεύει κανείς για να τον βλέπουν, για να προκαλεί την προσοχή όσων κάθονται γύρω του, άλλωστε τους γυρίζει συχνά την πλάτη. Οι χορευτές φαίνονται συνεπαρμένοι χωρίς όμως να δημιουργούν την εντύπωση ότι χορεύουν για να διασκεδάσουν ή να ξεδώσουν. Δεν πρόκειται ούτε για θέαμα ούτε για διασκέδαση, αυτό που συμβαίνει είναι μια μορφή τελετουργίας. Μια αναπαράσταση της κοινωνίας του χωριού, όπου ο καθένας ανεξαίρετα παίρνει με τη σειρά του τη θέση του κομπάρσου, του πρωταγωνιστή και του απλού θεατή. Κι έτσι, μ’ αυτή του τη συμμετοχή επισφραγίζει το γεγονός ότι ανήκει στη συγκεκριμένη κοινωνική ομάδα κι ασπάζεται τις αξίες της. Στο τέλος επιβεβαιώνεται κι ο ίδιος από την παρουσία των άλλων και φεύγει ήσυχος, έχοντας προηγουμένως πιστοποιήσει ότι τίποτα δεν άλλαξε στο βάθος κι ότι του χρόνου θα επαναληφθεί το ίδιο.

Η διατήρηση και η συνέχιση των συνηθειών του τόπου του, είναι οι μεγαλύτερες αξίες ενός χωρικού, γιατί όλη η κουλτούρα των αγροτικών πληθυσμών έχει ακριβώς αναπτυχθεί γύρω απ’ αυτούς τους δύο άξονες. Κάθε αλλαγή είναι εξ ορισμού ύποπτη, δεν γίνεται δεκτή, εκτός κι αν κάποιες εξωτερικές δυνάμεις την επιβάλλουν και δράσουν πιεστικά για αρκετό διάστημα ώστε να νικηθεί αυτή η αντίσταση. Δεν θα υιοθετήσουν ποτέ έναν καινούργιο χορό γιατί είναι «καινούργιος» ή γιατί είναι «καλύτερος» τέτοια κριτήρια δεν έχουν καμία βαρύτητα σε μια παραδοσιακή κοινωνία — αντίθετα με τη δική μας, τη σημερινή.

Συμβαίνει καμιά φορά κάποιος να παραγγέλνει ένα χορό που έτυχε να μάθει κάπου αλλού, αν φυσικά ο μουσικός ξέρει τη μελωδία, μπορεί να τον ζητάει σε κάθε ευκαιρία γιατί τον αγαπάει, και τότε τον χορεύει πότε μόνος του και πότε με τους φίλους του. Αυτός είναι ο χορός «του», ίσως να γίνει και ο χορός «του γιου του», ίσως να τον ονομάσουν μάλιστα «χορό του τάδε», γιατί αυτός ήταν πάντα ο μόνος που τον ζήταγε. Μετά το θάνατο του το πιθανότερο είναι να εξαφανιστεί, εκτός κι αν με τα χρόνια τον εκτίμησαν κι άρχισαν κι άλλοι να τον παραγγέλνουν, οπότε ίσως τελικά μπει στο κοινό ρεπερτόριο του χωριού. Να πώς εξελίσσεται η χορευτική παράδοση.

Ενα χωριό λοιπόν έχει έναν αριθμό διαφορετικών χορών — γύρω στους δέκα— που τους ξέρει όλος ο κόσμος. Θα ήταν σωστότερο βέβαια να μιλάμε για διαφορετικά βήματα παρά χορούς, στα μάτια ενός σύγχρονου εξωτερικού παρατηρητή. Γιατί όταν φέρνουμε σήμερα ένα χορό στο μυαλό μας, πρόκειται μάλλον για τα βήματα του κι όχι για του ίδιο το χορό, αν ξέρουμε να τα κάνουμε, πιστεύουμε ότι ξέρουμε και το χορό. Επί πλέον, ένας εκπαιδευμένος χορευτής εννοεί όλες τις κινήσεις του σώματος του αναπόσπαστα συνδεδεμένες με την τάδε η τη δείνα χορογραφία. Για ένα χωρικό όμως ο χορός είναι κάτι πολύ πιο σύνθετο που κλείνει μέσα του: το τραγούδι, τη μουσική, τη φορεσιά, τα ποτά, τις κινήσεις των παρευρισκομένων καθώς και όλη την κατάσταση μέσα απ’ όπου ξεπήδησε. Για τον παραδοσιακό χορό θα ήταν επομένως σωστότερο αντί να μιλούμε για τον άλφα ή βήτα χορό, να μιλούμε για το άλφα ή βήτα χορευτικό έθιμο ή —ακόμα καλύτερα— για την τάδε χορευτική συγκυρία.

Η τελευταία είναι και το πιο σημαντικό στοιχείο εξάλλου. Ο χορός αποτελεί αναπόσπαστο κομμάτι των εκάστοτε καταστάσεων, δεν μπορούμε να φανταστούμε μια ιδιαίτερη κατάσταση χωρίς το χορό της. Με την κάθε ιδιαίτερη ευκαιρία συνδέεται κι ένας ξεχωριστός χορός, ακόμα κι αν στα μάτια ενός σύγχρονου χορογράφου οι κινήσεις του σώματος είναι ολόιδιες σε δύο διαφορετικές συγκυρίες. Δεν χορεύουν ποτέ με τον ίδιο τρόπο για να γιορτάσουν ένα γάμο, μια θρησκευτική επέτειο, τις απόκριες ή διασκεδάζοντας απλώς στο καφενείο. 0 χώρος διαφέρει, τα άτομα που συγκεντρώνονται αλλάζουν, οι φορεσιές που φοριούνται, αλλά κι οι προετοιμασίες διαφέρουν όλες από τη μια περίσταση στην άλλη. Πάνω απ’ όλα αλλάζει η κυρίαρχη ιδέα κάθε φορά. Επομένως ούτε κι ο χορός μπορεί να είναι ποτέ ο ίδιος, όπως συμβαίνει με τη χορογραφία ενός σημερινού χορευτικού θεάματος, που μένει απαράλλαχτη και ανεπηρέαστη από το κοινό που την παρακολουθεί σε κάθε διαφορετική παράσταση.

Η ιστορία του χωριού διαφοροποιεί τις εκάστοτε καταστάσεις μέσα απ’ όπου γεννιέται ένας χορός, επηρεάζοντας κατά συνέπεια και τις κινήσεις του. Η ιστορία αυτή περικλείει το κλίμα, τη γεωγραφική διαμόρφωση, τις καλλιέργειες και τις υπόλοιπες ασχολίες, τα γειτονικά χωριά, το πέρασμα των ξένων και τα ταξίδια των ντόπιων στο εξωτερικό, τους πολέμους και τις καταστροφές. Κοντά σ’ αυτά έρχονται να προστεθούν άλλα τόσα στοιχεία δοσμένα από το μακρινό παρελθόν, που επικυρώνονται μέσα στην καθημερινή ζωή και μεταδίδονται στους νέους χάρη σε μια επαναλαμβανόμενη διαδικασία. Γιατί δεν πρέπει ποτέ να ξεχνούμε ότι πρόκειται για ένα κοινωνικό σύνολο σταθερό μέσα στο χρόνο και στο χώρο.

Το κλίμα ασκεί μια πρώτη επίδραση πάνω στο χορό. Το μεγαλύτερο μέρος του χρόνου μπορούν να συγκεντρώνονται στην ύπαιθρο για τις ετήσιες γιορτές, ενώ οι γιορτασμοί των γάμων γίνονται στα σπίτια και στις αυλές. Οι φορεσιές είναι αρκετά βαριές, ιδιαίτερα των γυναικών, με αποτέλεσμα να μην επιτρέπουν μεγάλη άνεση κινήσεων. Τα παπούτσια —που επηρεάζουν πολύ τον τρόπο που θα σταθεί το πόδι— είναι μεγάλα και χοντρά στην ηπειρωτική Ελλάδα κι ανάλαφρα στα νησιά. Τα βήματα, το παράστημα φέρνουν όλα τα σημάδια της καθημερινής ζωής, διαφέροντας έτσι απ’ τον τσοπάνο του βουνού στο γεωργό της πεδιάδας ή στο ναυτικό των παραλίων.

Η μουσική είναι μια άλλη έκφραση αδιαχώριστη απ’ το χορό. Είναι καθαρά λειτουργική, παίζεται για να εξυπηρετήσει το χορό κι όχι αυτοτελώς. Ο οργανοπαίχτης δεν παίζει ποτέ για να τον ακούσει ένα καθισμένο ακροατήριο· σε σπάνιες μόνο περιπτώσεις συνοδεύει παρέες που τραγουδούν στο τραπέζι. Ο οργανοπαίχτης είναι ένας άντρας του χωριού —ποτέ γυναίκα—πολύ συχνά γύφτος που έχει εγκατασταθεί εκεί σαν σιδεράς. Τον ξέρουν όλοι προσωπικά, παίζει πάντα γι’ αυτούς κι ο γιος του θα παίξει για τα παιδιά τους. Οι ίδιοι σκοποί, παιγμένοι απ’ τον ίδιο μουσικό για τους ίδιους χορευτές για μια ολόκληρη ζωή εξασφαλίζουν μια μοναδική σχέση μέσα στο χορό. Μια σχέση ολότελα παράξενη για τους σημερινούς ανθρώπους που έχουν συνηθίσει να χορεύουν διάφορες μελωδίες παιγμένες από άγνωστους μουσικούς.

Ο οργανοπαίχτης παίζει με τα μάτια καρφωμένα πάνω στο χορευτή, τον γνωρίζει πολύ καλά προσωπικά, ξέρει τις προτιμήσεις του. Γνωρίζει ακόμη την οικογενειακή του ιστορία, τις έγνοιες και τις φιλοδοξίες του, ξέρει με λίγα λόγια για ποιους λόγους χορεύει, θα κολακέψει έτσι αν χρειαστεί τη ματαιοδοξία του ή την επιθυμία του να γίνει αρεστός, θα τον σπρώξει με τη μουσική του να επιδείξει τη σβελτάδα του, θα τον βοηθήσει να ξεχάσει τα προβλήματα του. Ο χορευτής ακούει και καταλαβαίνει τη μουσική σαν να την έπαιζε αυτός ο ίδιος. Αντιλαμβάνεται ακόμη και τα πιο ανεπαίσθητα μηνύματα που του στέλνει το όργανο, κατέχει πολύ καλά πώς να τα αποκρυπτογραφεί, έτσι όπως ξέρει να προβλέπει τον καιρό από διάφορα σημάδια που του δίνει η φύση. Η αντίδραση του είναι άμεση.

Αυτή η βαθιά επικοινωνία τους αποτελεί κομμάτι του χορού. Οι μουσικοί του χωριού παίζουν πολύ άσχημα μέσα σ’ ένα στούντιο ηχογραφήσεων χωρίς τους χορευτές τους, μόνο μετά από πολύωρο ή κι ολονύκτιο ασταμάτητο παίξιμο μέσα σε αυθεντική ατμόσφαιρα γλεντιού παίζουν πραγματικά καλά. Είναι γνωστό ότι μια μεγάλη γιορτή μπορεί να κρατήσει ακόμη και τρία μερόνυχτα, με κόσμο να μισοκοιμάται όρθιος κι άλλον να αποσύρεται διακριτικά για να ξεκουραστεί λίγο στο σπίτι του, ώστε αργότερα να επιστρέψει.

Ο χορός στο χωριό είναι τόσο στενά συνδεδεμένος με κάποια δοσμένη κοινωνική κατάσταση που δεν μπορεί να υπάρξει μόνος του έξω απ’ αυτήν. Εκεί ο κόσμος δεν χορεύει για να χορέψει, ούτε όταν είναι μόνος του, ούτε για μια μεγάλη χαρά ή μια μεγάλη λύπη. Προηγείται μια σειρά από συλλογικές προπαρασκευαστικές δραστηριότητες. Πρόκειται για έναν κοινωνικά οργανωμένο χορό, με κανονισμένη διαδικασία, εφόσον αποτελεί κομμάτι μιας κουλτούρας όπου όλα επαναλαμβάνονται με τη μορφή της τελετουργίας.

Σε μια γιορτή οι χορευτές είναι ιεραρχημένοι όπως και τα τραγούδια. Το γλέντι αρχίζει με τον τάδε χορό και τελειώνει με το δείνα. Στην Κύπρο επιβιώνουν σήμερα χορευτικοί σκοποί που αντί για όνομα λέγονται «ο πρώτος», «ο δεύτερος» κλπ. Αυτός ο προγραμματισμός ποικίλλει κι είναι λιγότερο ή περισσότερο απόλυτος ανάλογα με την περιοχή- συνήθως στην αρχή παίζονται οι επίσημοι χοροί, ενώ οι γρήγοροι, οι χαρούμενοι αφήνονται στο τέλος. Κάθε συντελεστής —μουσικός ή χορευτής— ξέροντας το σενάριο από πριν, προετοιμάζεται καλύτερα για το ρόλο που θα παίξει. Για άλλη μια φορά θέλουν να περιορίσουν το απρόοπτο και να εξασφαλίσουν τη συνέχιση του ήδη γνωστού.

Ακόμη πιο σημαντικό από την τάξη των χορών είναι η τάξη των χορευτών στον κύκλο. Στους επίσημους χορούς, στο ξεκίνημα κυρίως της γιορτής, ο καθένας έχει μια αυστηρά καθορισμένη θέση μέσα στον κύκλο. Η σειρά των θέσεων ποικίλλει πολύ από περιοχή σε περιοχή κι εμείς ανακαλύψαμε αρκετές δεκάδες τρόπων, σύμφωνα με τους οποίους τοποθετούνται οι χορευτές σε σειρά. Για παράδειγμα, μια διαδεδομένη συνήθεια στην ‘Ηπειρο είναι: να στέκουν πρώτα οι παντρεμένοι κατά σειρά ηλικίας, ύστερα οι ελεύθεροι, με τελευταίο τον πιο νέο, έπειτα οι παντρεμένες και τέλος οι κοπέλες. Μια άλλη συνήθεια πάλι, που συναντούμε σε μερικά νησιά, είναι η τοποθέτηση τους κατά οικογένειες: ξεκινώντας απ’ τον παππού και τη γιαγιά, ύστερα το μεγάλο γιο και τη γυναίκα του μαζί με τα παιδιά τους, τον εγγονό με την οικογένεια του κ.ο.κ. και μετά από αυτήν να συνεχίζεται ο κύκλος με μια άλλη οικογένεια.

Η θέση τους μέσα στο χορό αντιπροσωπεύει συμβολικά και τη θέση τους μέσα στην κοινωνία. Κάποιος που ξενιτεύτηκε στα νιάτα του και επιστρέφει πια συνταξιούχος στο χωριό του, θα βρει τη θέση του στον κύκλο να τον περιμένει έστω και ύστερα από σαράντα χρόνια. Ο πρωτοξάδελφος πάλι που έρχεται στο χωριό για πρώτη φορά προκειμένου να παραστεί στους γάμους της ξαδέλφης του, θα έχει δικαιωματικά τη θέση του στον εναρ κτήριο χορό του γλεντιού, ορισμένη ανάλογα με το βαθμό συγγένειας. Μέσα σ’ όλα αυτά τα στοιχεία βρίσκεται ίσως κι η εξήγηση της εκπληκτικής αδυναμίας που τρέφουν μετανάστες για το χωριό τους, ακόμη κι ύστερα από μια ολόκληρη ζωή στην πιο απόμακρη ξενιτιά. Η θέση του καθένα στο χωριό κρατιέται πάντα φυλαγμένη, κι η έμπρακτη απόδειξη είναι η θέση του που διατηρείται γι’ αυτόν στο χορό, παρά τη μακρόχρονη απουσία του. Γυρίζοντας ξαναβρίσκει στο πλευρό του τα ίδια άτομα, κι αν μάλιστα ζήσει μέχρι τα βαθιά γηρατειά θ’ αξιωθεί να μπει στην πρώτη θέση του κύκλου και να σύρει το χορό ακολουθούμενος από ολόκληρο το χωριό.

Το πνεύμα της ισότητας φαίνεται από τη δυνατότητα του καθενός να σύρει το χορό σε κάθε γιορτή τουλάχιστον μια φορά. Αυτό έχει γίνει σε τέτοιο βαθμό κατεστημένο δικαίωμα, που έχει πάρει πλέον τη μορφή ενός καθήκοντος, με αποτέλεσμα κάποιος που δεν το εκπληρώνει να κινδυνεύει να παρεξηγηθεί.

Αν η συμμετοχή είναι μεγάλη, ο γερο-μουσικός φροντίζει ώστε να σύρει ο καθένας από τουλάχιστον μισό χορό, πριν ξαναρχίσουν οι παραγγελίες. Αν δει πως κάποιος επιμένει πετώντας του χρήματα για να χορέψει περισσότερο απ’ όσο του αναλογεί, είναι υποχρεωμένος να του αρνηθεί.

Γιατί κάθε χορός πληρώνεται από το χορευτή. Σηκώνεται με τη σειρά του, πλησιάζει τους μουσικούς, παραγγέλνει το χορό (ή μάλλον το τραγούδι) της αρεσκείας του και παίρνει θέση επικεφαλής του. Οσο χορεύει, όλο και πετάει χρήματα στους μουσικούς. Οι φίλοι ή οι γονείς του πετούν κι αυτοί για να τους ενθαρρύνουν να παίξουν καλύτερα για χάρη του και να δείξουν την υποστήριξη τους. Ετσι επισφραγίζεται κι απομυθοποιείται ο άμεσος σύνδεσμος μεταξύ χορευτή και μουσικού. Το δικαίωμα να κατέχει κάποιος την πρώτη θέση αγοράζεται σαν οποιοδήποτε εμπόρευμα. Ο χορός έχει λοιπόν και χρηστική αξία, που πρέπει να αποτιμηθεί. Ο μουσικός του χωριού δεν διατείνεται τον καλλιτέχνη, παραμένει και στη γιορτή ένας απλός τεχνίτης, όπως άλλωστε είναι και τον υπόλοιπο καιρό, όταν ασκεί το καθημερινό του επάγγελμα. Σιδεράδες συχνά, που πληρώνονται με το κομμάτι για κάθε πέταλο αλόγου που θα φτιάξουν, οι μουσικοί των γλεντιών δεν βλέπουν το λόγο γιατί να μην πληρωθούν και για κάθε κομμάτι που θα παίξουν για να χορευτεί.

Παλιότερα, σε μια εποχή που τα χωριά δεν είχαν ακόμη συνδεθεί με δρόμους με τις πόλεις και η εμπορευματική οικονομία δεν είχε ακόμη αναπτυχθεί σ’ αυτά, ο μουσικός πληρωνόταν με αυγά, κοτόπουλα, σακιά σιτάρι, λάδι. Και στις περιπτώσεις όμως που πληρωνόταν εξ αρχής με συμφωνία, οι χορευτές δεν μπορούσαν να αντισταθούν στην επιθυμία να πετάξουν και μερικά νομίσματα επιπλέον τις στιγμές της μεγάλης συγκίνησης. Τα κύρια προσόντα που αναγνωρίζονται σε ένα μουσικό είναι: ο πλούτος του ρεπερτορίου του, η αντοχή του, η δύναμη στο παίξιμο, το γέμισμα και η παραλλαγή στη μελωδία με ποικίλματα, και πάνω απ’ όλα η ικανότητα του να μπαίνει στην καρδιά του χορευτή και να του αποσπά έντεχνα τις στερνές του οικονομίες.

Τα χρήματα χρησιμεύουν στην ανταμοιβή των μουσικών, στην παρότρυνση τους να παίξουν καλύτερα και —αυτά που προέρχονται από φίλους— στο να τιμήσουν το χορευτή, χωρίς όμως να μπορούν και να διαταράξουν το πνεύμα της ισότητας που χαρακτηρίζει ιδιαίτερα τις κοινωνίες αυτών των χωριών ακόμη κι ο πλουσιότερος άνδρας θα χορέψει όσο και ο πιο φτωχός μέσα στον κοινό χορό, έστω κι αν πετάξει περισσότερα λεφτά. Θα μπορέσει βέβαια αργότερα, στην πορεία της βραδιάς, να παραγγείλει παραπάνω προσωπικούς χορούς για λογαριασμό του. Οσο ο χορός είναι ένα δικαίωμα για όλους, άλλο τόσο είναι και υποχρέωση, ένα είδος δημόσιου αφιερώματος στην συλλογικότητα του χωριού. Ο καθένας οφείλει να σύρει τουλάχιστον ένα χορό, τόσο πολύ που σ’ ορισμένες περιπτώσεις μπορεί και να πληρώσει συμβολικά κάποιον άλλο να χορέψει στη θέση του. Μια γιορτή που γίνεται χωρίς χορούς, εξαιτίας κάποιου μεγάλου πένθους ή μιας μεγάλης σιτοδείας, αποτελεί κακό οιωνό για τη χρονιά που θ’ ακολουθήσει.